Martyn Percy: Embrace the “Tutufication” of the Church of England Part 4

February 21, 2022

Pauline’s poem

March 2, 2022What if the boot is on the other foot? We’ve had a couple of centuries of atheists arguing that science undermines belief in God. But what if it undermines belief in atheism?

This post is an edited version of a sermon I preached at All Hallows Leeds. It argues that our secular culture doesn’t actually do without gods. It gets rid of traditional gods, but creates new ones. It does this by treating information as though it was a force. By doing this, it camouflages the fact that it can’t explain the forces we depend on.

Default atheism

As far as anthropologists know, right up to the 18th century every society conducted public debate within the context of whatever gods they believed in.

Today it’s different. Our public life is based on a kind of default atheism. You are allowed to believe in God, but only as a private matter. Public decisions have to be made on observable scientific evidence, without reference to God.

Early defenders of God argued that science can’t explain everything. A favourite was the eye. It seemed too complex to have evolved. It must have been created by God. This is the ‘God of the gaps’ argument. It was a bad argument: later on science did explain it.

Nevertheless science does have limits. What it can do is limited by the methods it uses: observing regularities and testing hypotheses.

Your desert island choice

To explain my point, here is a story. You are stranded alone on a desert island. Sand, a few rocks, a palm tree in the middle. No sign of human habitation. Absolutely nothing to eat or drink. All around is the sea, as far as the horizon.

You go to sleep. In the morning you wake up hungry. You can smell something. You open your eyes. On a rock next to you, there is a plate with a fried egg, bacon, sausage, hash brown, mushrooms and baked beans. Next to it is a glass of fruit juice and a mug of hot coffee.

So you scoff the lot. And you wonder how it got there. You look round the island. You don’t see any footprints in the sand. You don’t hear any voices, or even a helicopter in the sky. Not even a ship on the horizon. You can’t understand how it got there.

The next morning exactly the same thing happens. And the morning after. Day after day this food keeps turning up, and however hard you look there is still no sign of who is putting it there.

After a few weeks you start taking the food for granted. You assume that tomorrow’s breakfast will arrive in the normal manner. One day the sausages are a little over-cooked and instead of your original amazement that there is anything there at all, you feel a bit disappointed. The regular arrival of the food has become something to take for granted.

At this point, do you say to yourself ‘This is the way things are on this island. Now I understand.’ Or are you still puzzled about how it gets there?

Of course you would still be puzzled. The regularity is one thing, the cause another.

It’s the same with the scientific laws of nature. These laws are the regularities we observe. What causes them is another matter.

The forces

Before the 18th century, all over the world (as far as we know), every society accepted that humans have neither the power nor the knowledge to produce and maintain this world. So it must be maintained by forces more powerful and more intelligent than humans.

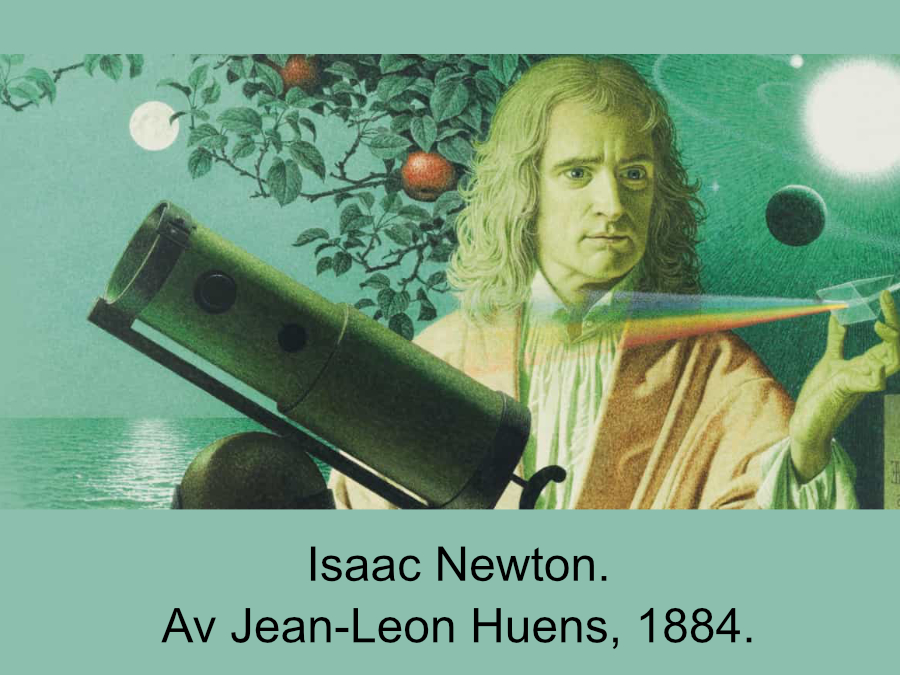

The modern idea of laws of nature was worked out in the 17th Century, chiefly by René Descartes, Robert Boyle and Isaac Newton. All of them worked on the basis that the regularities of nature are caused by God.

The breakthrough that made modern science possible was the consensus that a consistent God imposes regular laws on the universe. Once they had agreed that, it then made sense to do scientific experiments.

If you pick up something in your hand, hold it in front of you, and then move your fingers apart, you know what will happen. It will fall to the floor. That’s gravity. If you’ve ever learned any physics, you may have been taught that gravity is a force. For practical purposes this is a good enough description.

But when we want to understand how the whole system functions, we need to be more precise. When Isaac Newton discovered the law of gravity what he actually discovered was that the rate at which things drop to the ground is the same as the rate at which planets orbit the sun. He described it as an equation. Equations don’t make anything happen. They just describe what happens. Newton was quite clear that what he had discovered was an equation, not a force. But there must be a force there. As far as he was concerned, the force was God.

Atheism

But what if there is no God? 50 years after Newton, some European intellectuals were breathing a different air. They argued about whether God existed, but were quite sure that the laws of nature are absolutely unbreakable.

One of them was the philosopher David Hume. As an empiricist he was committed to working out how the world works by observing and measuring what happens. But he got stuck with causation, because we never see it.

When you moved your fingers apart and saw that thing drop, you will have noticed two movements: of your fingers, and the thing dropping. What we observe is the correlation. Scientific theories map the correlations by statements of the type ‘When x happens, y happens’. We infer that x causes y, but we never see the causal process. We never see a force.

If you find it difficult to believe this, it’s probably because we are all used to treating correlations as though they were forces. After all, for practical purposes the difference doesn’t matter. But when we pay attention to the fact that a correlation isn’t a force, we can see why Hume was so puzzled.

He answered his puzzle in what I guess is his most famous text:

Since reason is incapable of dispelling these clouds, Nature herself suffices to that purpose, and cures me of this philosophical melancholy and delirium, either by relaxing this bent of mind, or by some avocation, and lively impression of my senses, which obliterate all these chimeras. I dine, I play a game of backgammon, I converse, and am merry with my friends; and when, after three or four hours’ amusement, I would return to these speculations, they appear so cold, and strained, and ridiculous, that I cannot find in my heart to enter into them any further.

In other words, he gave up; and thereby set the tone for the subsequent philosophy of science.

So what’s happening? The 17th century scientists worked on the basis that the laws of nature are regularities caused by God. In the 18th century, as secularism kicked in, scientists carried on exploring the regularities, but stopped talking about God as the cause. This left them with no account of the cause.

Ever since then, the laws of nature have been treated as though they were not just regularities but causes as well. Treating them as causes is not a scientific discovery. It’s an assumption, assumed because without it atheism doesn’t work.

This is what I mean by saying atheism treats information as though it was forces, and in this way it creates new gods. It does the same with other processes as well, but just this one is enough for now.

Conclusion

Whether we are atheists or believers, we live our lives in the context of invisible forces. Actually, we can’t explain them. Our scientists provide maps of what some of them usually do. This is a great achievement. It has helped in many ways. It has been achieved, largely, by huge amounts of systematic research.

But also by the philosophical presuppositions shared by early modern theorists and experimenters. If they hadn’t believed in a single, consistent, benevolent god running the universe in a regular way, doing experiments would have been a pointless exercise and modern science would never have got going.