Girard, Johnson and how we love to hate scapegoats

January 30, 2022

Phil Groves: LLF, the Anglican Communion and Institutional racism

February 8, 2022We are incredibly grateful to the Very Revd Prof Martyn Percy for this series of reflections, which will be added to in the lead up to Lent.

One: Finding Our Pulse and Heart

Two: Finding Our Substance and Spine

Three: Finding Our Courage and Conviction

Four: Finding Our Wisdom and Discernment

Finale: At the End of the Rainbow – Finding Our Home

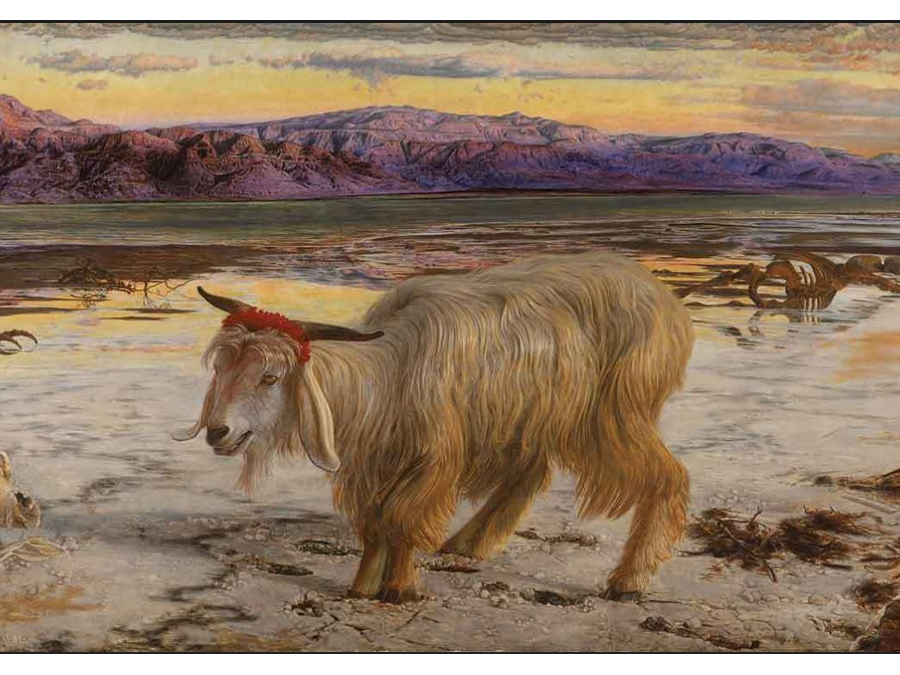

The Times carried Canon Mark Oakley’s letter (above) on January 1st. In a timely way, Canon Oakley’s letter suggests that part of the reason the Church of England’s pulse is so weak at present is that Bishops are unhappy: mired in downsizing (whilst also being centrally cast and scripted to talk about nothing other than new growth, more congregations, etc.), safeguarding (unable to see the wood for the trees) and finance (facing pressure to downsize, yet speaking only of more growth, as though this still brings cheer to the faithful). As a result, we have lost honest and imaginative thinking, with integrity mislaid along the way. Our ecclesial culture is dominated by a kind of Orwellian “committee-speak”, which resonates with nobody expect those who have developed fluency in such Ecclesial-Esperanto. The numerous errors and the more occasional corrupt aspects of church-life are sent off to be laundered by professional PR merchants. Yet the trouble is, and as Lady Macbeth discovered, some stains are tricky to shift, no matter how many times you wash your hands. The public also see the dirty laundry, and whilst Febreezing the Church masks the odours for a while, the pong persists.

The film The Wizard of Oz was based on an earlier allegorical tale by Frank Baum, which originated as a critique of late 19th century American society and an insatiable appetite for gold-rush, with the promise of instant riches. Like Bambi, Hollywood and Disney has not always served us well. Felix Salten’s Bambi: A Life in the Woods (1923) was an allegorical tale warning the world that Jews would be hounded, hunted dehumanised and murdered in the decades ahead. Far from being a children’s story, Bambi was about the precarious situation and inhumane treatment of Jews and other minorities that was to become horrifyingly apparent to the world. The Wizard of Oz is also a social and moral allegory.

Thus, in Frank Baum’s tale, ‘Oz’ literally means ounce (i.e., ‘oz.’), and the Yellow Brick Road is akin to the English folktale of Dick Whittington for whom “the streets of London are paved with gold”. This road lures the foolish, who are represented by archetypes: a Scatty Scarecrow (poor rural farmers, lacking wisdom), a Tin Woodman (greedy industrialists decimating the environment to mine the gold), a Cowardly Lion (those lacking moral courage) and Dorothy (the gullible and innocent).

In the book, the four, and accompanied by Toto the dog, head off for the holy grail of personal wealth. The film reflects Baum’s story on the surface, but much of the deeper allegory is lost in translating the book to cinema. That said, when the party eventually reach Oz, the journey proves to have been worthless. The Wizard of Oz turns out be a powerless old man, booming out instructions from behind a curtain. He’s been trapped in a web of deceit he spun himself. It turns out he needs rescuing and saving too.

Perhaps we should not labour the allegory, but if you have ever asked your Bishop for a decision or statement of some kind that might require them to act with authenticity or integrity, you will have already encountered Oz. Smoke, mirrors and amplified committee-speak billow out. We were led to this place along a yellow brick road that promised untold stories of growth, an Emerald City and instant success. Dorothy, the Scarecrow, the Tin Woodman and the Lion are all deserving of our empathy and sympathy, not least because they are lost souls, frightened and rather clueless.

Yet each of the four main characters represents something in us all – the yearning to know our place in the world, have our own home, and for self-knowledge, as well as our hunger for courage, wisdom and compassion. Baum’s storytelling relied on the deep spiritual tropes he was immersed in. He was a nominal Anglican, who became a member of the Theosophical Society, which partly explains his fascination with enchantment. We also note the strongest characters in his novels are female. It should perhaps not surprise us that Baum was an early advocate of feminism, and worked tirelessly for women’s suffrage.

Baum’s story is riddled with moral, spiritual, and theological references. The name Dorothy means “gift of God”. There were fourteen tales from Oz penned by Baum, each of them indebted to established literary tropes from John Bunyan, St. John’s holy city, and much else. In Baum’s book, the Good Witch of the North gives Dorothy a pair of silver slippers (rendered ruby-red in the film). The silver slippers have a double meaning – silver as a precious commodity, coveted by the Wicked Witch (literally rendered green with envy in the film – nothing left to chance!). But the silver slippers are also the equivalent of a scallop shell – the means of pilgrims finding direction – which the Good Witch gives Dorothy by bestowing a baptismal-blessing kiss upon her forehead. Famously, in the book and the film, the Wicked Witch fears the water (even to the extent of carrying an umbrella in Baum’s novel, rather than a broomstick).

In this series of five reflections, we leave Toto to one side, and explore what a “Tutufication” of the Church of England might mean for us today. Taking our cue from Frank Baum’s Oz and the four journeying characters, our five reflections consist of:

- Finding Our Pulse (More Humanity and Less Robot?)

- Finding Our Spine (More Substance and Less Straw?)

- Finding Our Voice (More Courage and Less Timidity?)

- Finding Our Place (More Wisdom and Less Naivety?)

- Finale: At the End of the Rainbow – Finding Our Home.

Each of the reflections comes with a small collation of five quotes from Desmond Tutu, a bible passage from the Gospel of Luke, and some suggestions for personal or group reflection and further exploration. For this series, no knowledge of the Wizard of Oz is presumed, and we have not assumed that readers will know much about Desmond Tutu either (other than perhaps by reputation). Our aim is to help prompt some different thinking about a church rooted in Tutufication: one that exhibits compassion, substance, courage, wisdom, fortitude, discernment, risk, strength and gentleness – and with an enormous capacity to journey, as all pilgrims do – and not be swayed by shortcuts or promises of instant results.

Our faith is not some journey to an Emerald City, and nor do we follow some golden path. Our end-point is, rather, another city, where there is no darkness or pain; all suffering and war are ended; equality, truth and justice shine out; and the lion and the lamb are at peace. A whole country of truth and reconciliation was what Tutu strived for. Our aspiration is more modest. We are merely seeking the possibility of a church that lives in truth, and understands the burdens and blessings of belonging together.

One: Finding Our Pulse and Heart

Bible Passages and Questions: Lost Causes (Luke 15)

- Sometimes, finding the pulse and the heart of the church is not easy – yet the heartbeat of the body must be love for the lost. As Jesus is the Body Language of God, for whom does God’s heart ache in your community and our society today? Can you check your pulse on this, and hear your heartbeat?

- How can our churches be communities of forgiveness, reconciliation and ever-enduring faith, hope and love (for/with others, and in God)?

- When does the church become the Body Language of God?

Desmond Tutu:

- Do your little bit of good where you are; it is those little bits of good put together that overwhelm the world.

- We may be surprised at the people we find in heaven. God has a soft spot for sinners. His standards are quite low.

- When we see others as the enemy, we risk becoming what we hate. When we oppress others, we end up oppressing ourselves. All of our humanity is dependent upon recognizing the humanity in others.

- We must be ready to learn from one another, not claiming that we alone possess all truth and that somehow we have a corner on God.

- We are made for goodness. We are made for love. We are made for friendliness. We are made for togetherness. We are made for all of the beautiful things that you and I know. We are made to tell the world that there are no outsiders. All are welcome: black, white, red, yellow, rich, poor, educated, not educated, male, female, gay, straight, all, all, all. We all belong to this family, this human family, God’s family.

Discussing the quotations above, how do we begin to love the lost causes in society? How can we care for and value the ones of whom society despairs? What more can the church be doing to model God’s reckless, inclusive love?

Reflection: Lost Causes

The Parable of the Prodigal Son is a parable about a prodigal father – who lavishly wastes his love on an undeserving son. But he is a bit of a King Lear. It is not his feast to give. Nor his ring to give. That is what ‘prodigal’ means. The dictionary says that ‘prodigal’ is wastefully or recklessly extravagant: prodigal expenditure; giving or yielding profusely; lavish (usually followed by of or with): prodigal of smiles; prodigal with money; lavishly abundant; profuse: nature’s prodigal resources. Related words are profusion absurdity, lavishness, outrageousness, waste, exaggeration, overindulgence, extravagance, excess, wastefulness, improvidence, profligacy, folly, recklessness…

But on whose part? We are sometimes not well-served by our standard way of reading the text, which assumes the father is God, the errant younger son standing as a cipher for us sinners – granted, we only claim honorary status; and the older son as a code for a curmudgeonly church that prefers to ration its grace and mercy. But I want to suggest to you that the father is wasteful. He divides his inheritance – a bit like a rash King Lear, but this time not three daughters, but rather two sons. He is negligent, in other words…

The father is profligate – he divides the business in a way that is prodigal, quite wasteful, actually. He’s a poor role model. The younger son is profligate. As the saying in Yorkshire goes, he spends the money on wine and gambling, and the rest he wastes on women. The older son is the opposite of wasteful, it seems. The father, at the end of the parable, kills a calf that is not his; throws a feast that the older son is paying for, and gives a ring to the younger that must belong to the elder.

This is the parable of the lost family – and where is the mother to bring some sense and prudence to all this? The father and the younger son have no idea how really to manage. They are both profligate. This family needs to talk about money! They need financial mediation. I wonder if you have ever pondered just how elemental money is? Nearly all the language we have to describe it corresponds with the ancient four elements: Earth, Air, Fire and Water. Let me illustrate this:

Earth/Ground – bank(ing); build-up; security; stable; stock; floor; shockwave, etc.

Wind/Air – inflation; deflation; savings blown; financial gloom; uplift, downturn, etc.

Fire – money to burn; financial meltdown; consume; overheated economy; fire sale, etc.

Water/Liquid – fluid assets; profits evaporate; economy frozen; drowning in debt, etc.

Understood like this, the younger son commits a kind of reverse-perverse alchemy, converting gold to worthless ash. His literal elemental sin is to turn the solid into liquid; and like a locust, he burns through all the money; he ends up drowned in debt; he vaporizes his inheritance. So he must return home. But yet he journeys back in disgrace, having shamed his father. He has lost his sonship, but hopes to have some place in the extended household. There, he can at least live, albeit with the permanent stains of shame and humiliation. This is why the father’s restoration of his son is such a radical act: it is unwise, degrading, and shameful. Having been taken for one ride already and shamed by his son, the father merely compounds the dishonour by treating his son as an heir, as before.

We begin with these rather teasing cultural references because this parable is one of the deepest we have in the gospels. Martin Luther said that if this parable was all we had in the New Testament, it would be enough. Artists have painted it; sung it; filmed it; poets have scripted it. So have novelists. To begin with, it is about Shame Culture in ancient near east society – and we often miss this when we read it. It is easy for us to talk about what we feel guilty about – forgetting birthdays or anniversaries; a missed appointment; a stolen treat.

But shame is different. All three characters in the parable have shame: the father and the younger son, for sure; but also the older son, for the shame of how the parable ends, and for having his prudent husbandry up-ended. We rarely talk about what we are ashamed of. Even with those who know us best and love us most, it is costly to say what shames us. For we risk the disgust, censure and withdrawal of the one who loves us. Suppose my shame causes their rejection of me? So we keep it in. It festers.

The son felt not guilt, but shame. For he knew he had shamed his father, publicly, and amongst his neighbours and peers. True, the father may not be ashamed of his son. But by losing his son to idle and profligate spending, he had been shamed amongst his community, peers and family. The father had been diminished in the eyes of his older son, family and friends. I expect the older son thought he was doing his father a favour by staying on at the farm. Charity from him? Perhaps a kind of condescending kindness, but it is awkward and to some extent, possibly patronising. He is shamed by this feast: shame is everywhere.

In some sense, then, the father’s gesture to the younger son is therefore revolutionary in character. Because he does not deal with guilt by forgiveness. No. Rather, he deals with shame by redemptive, excessive public celebration. The only way to really smash shame and restore a person. Jesus does it with the woman caught in adultery. The woman who anoints him at the house of Simon the Pharisee, and the Samaritan woman at the well in the Gospel of John. In each case, shame is smashed – conquered by unqualified love and public vindication. Humiliation is addressed, redeemed and destroyed.

That’s why the older son and brother can’t cope. Because deep down, he is a Pelagian. That is the heresy where you earn your salvation. As though God were running some secret club-card loyalty bonus scheme. You join the scheme when you join the church. It entitles you to extra grace; special offers on prayers; extra portions of God’s love and entitles the card-holder to feel ever so slightly…smug. Spiritually, I mean. To get the club-card, you join a church. And provided you take your turn of duties (i.e., works that earn points) – coffee rota, visiting, PCC, and other duties – the rewards are yours. The best schemes are run by proper tribes like Anglo-Catholics and Evangelicals. These really are clubs.

The Parable of this Prodigal Family says: “nuts to that”! The love of God is a pardon for fools. People who have got themselves in a right old mess. The woman at the well; the one caught in adultery – and the one who can only think of giving Jesus a sensual, scented pedicure, and use her hair to wipe him down. She isn’t going to seduce him, feet first, in front of all these people. But she has to show her love somehow. What does Jesus say to each of these three women: “You are forgiven”. You were never, ever, lost to God. No-one is. Nothing is. There are no Lost Causes for God. None.

You were lost, half-dead, yet you started home. But long before you were within sight of home, the parent who is God left home, and ran out to find you greet you. That is the gospel. You were always loved. And even though you were lost, God chose to come and find you, and bring you home, and feast at his table. Not as a hired hand, but as the daughter and son he always cherished and loved. So, maybe the parable says that perhaps forgiveness is possible after all. Partly for this reason, I admire Harry Smart’s poem, ‘A Fool’s Pardon’ (Harry Smart, A Fool’s Pardon, London: Faber & Faber, 1995, p. 7) reminding us of what this Kingdom of God Project is all about:

Praise be to God who pities wankers

and has mercy on miserable bastards.

Praise be to God who pours his blessing

on reactionary warheads and racists.

For he knows what he is doing; the healthy

have no need of a doctor, the sinless

have no need of forgiveness. But, you say,

They do not deserve it. That is the point;

That is the point. When you try to wade

across the estuary at low tide, but misjudge

the distance, the currents, the soft ground

and are caught by the flood in deep schtuck,

then perhaps you will realise that God

is to be praised for delivering dickheads

from troubles they have made for themselves.

Praise be to God, who forgives sinners.

Let him who is without sin throw the first

headline. Let him who is without sin

build the gallows, prepare the noose,

say farewell to the convict with a kiss.

I have only a few points to conclude. First I think we should notice from the context that the Lost, or Prodigal, Son is the last in a trilogy of parables about lost things. It belongs with the stories of the Lost Sheep and the Lost Coin. These parables aren’t placed together by accident; the gospel-writer means us to read them side-by-side. Second, I think we ought to notice some of the differences between these parables as well as the similarity of theme. Now there are many such differences, but let me mention just one – value. The missing sheep never loses its value; it never ceases to be a sheep. However silly it might seem to risk ninety-nine sheep for the sake of one; at least the one sheep is worth having! The missing coin never loses its value; it never becomes an ex-coin. But the prodigal son is rendered valueless in terms of the norms of that society. The son is socially dead, and by the customary rules, he cannot be sought or found, since he is no longer a son. But to God, everyone has value, and everyone is equally loved, always. Lost or Found.

6 Comments

[…] Percy Modern Church Twenty-Tutu (2022) is the Year for Leaving Oz Behind – Embrace the “Tutufication” … The first of a series of reflections in the lead up to […]

[…] Finding Our Pulse and Heart Two: Finding Our Substance and Spine Three: Finding Our Courage and Conviction Four: Finding […]

[…] One: Finding Our Pulse and Heart Two: Finding Our Substance and Spine Three: Finding Our Courage and Conviction Four: Finding Our Wisdom and Discernment Finale: At the End of the Rainbow – Finding Our Home […]

[…] One: Finding Our Pulse and Heart Two: Finding Our Substance and Spine Three: Finding Our Courage and Conviction Four: Finding Our Wisdom and Discernment Finale: At the End of the Rainbow – Finding Our Home […]

[…] One: Finding Our Pulse and HeartTwo: Finding Our Substance and SpineThree: Finding Our Courage and ConvictionFour: Finding Our Wisdom and DiscernmentFinale: At the End of the Rainbow – Finding Our Home […]

[…] One: Finding Our Pulse and Heart Two: Finding Our Substance and Spine Three: Finding Our Courage and Conviction Four: Finding Our Wisdom and Discernment Finale: At the End of the Rainbow – Finding Our Home […]