Adrian Thatcher’s Introduction to Modern Church’s 2022 Conference

August 11, 2022

Peter Liddell – The Fall of Kabul: An Unhappy Anniversary

August 17, 2022This post is the first of two responses to William Cavanaugh’s excellent The Myth of Religious Violence (2009). It has challenged my understanding of the ‘religious wars’ of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries; but it also sheds light on today’s international conflicts.

It is a myth, Cavanaugh tells us, in both the usual senses: an untruth, and a moral narrative justifying a particular establishment.

The untruth is that the wars of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries consisted of Catholics and Protestants killing each other because of their religious disagreements. The moral narrative is that public religion is dangerous. The solution was the rise of the nation state. Being religiously neutral, the nation state can be trusted to have a monopoly on the means of violence and thereby tame religious passions.

This story… has a foundational importance for the secular West, because it explains the origin of its way of life and its system of governance. It is a creation myth for modernity. Like the ancient Hebrew Genesis or the Babylonian Enuma Elish, it tells a story of the overcoming of primordial chaos by the forces of order. The myth of the wars of religion is also a soteriology, a story of our salvation from mortal peril. In other words, the story of the wars of religion has a crucial legitimating function for the secular West… The myth of religious violence is inextricably bound up with the legitimation of the state and its use of violence.

Why the myth is wrong

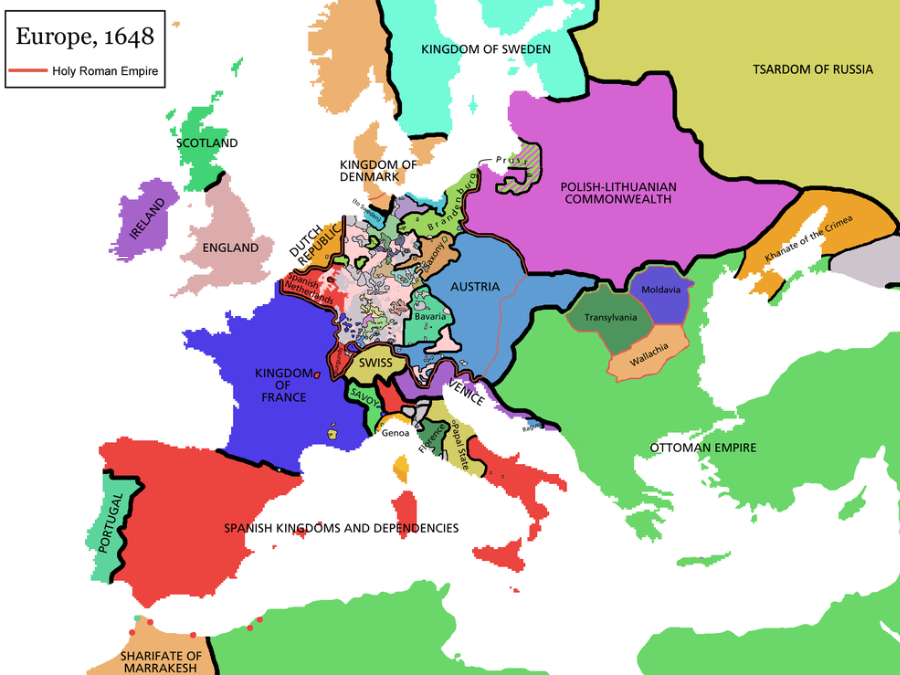

The myth is untrue on two counts. The first is easy to explain. Those wars of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries were not characterised by Catholics fighting Protestants. Catholics fought Catholics, Protestants fought Protestants. Rulers made alliances in the time-honoured manner of trying to be on the winning side regardless of the religious beliefs of their allies. For example:

Cardinal Richelieu and Catholic France intervened in the Thirty Year’ War on the side of Lutheran Sweden, and the last half of the Thirty Years’ War was essentially a battle between the Habsburgs and the Bourbons, the two great Catholic dynasties of Europe.

The second reason is that the concept of ‘religion’ as a distinct cultural phenomenon, distinct from ‘society’ or ‘politics’, didn’t even exist at the beginning of those wars. It was a product of the wars:

In the sixteenth century, the modern invention of the twins of religion and society was in its infancy; where the Eucharist was the primary symbol of social order, there simply was no divide between religious and social or political causes. This means that there is no way to pinpoint something called religion as the cause of these wars and excise it from the exercise of public power.

The rise of nation states

Cavanaugh argues that the real reason for the European wars of the 15th-17th centuries was the rise of the nation state.

The process of state building, begun well before the Reformation, was inherently conflictual. Beginning in the late medieval period, the process involved the internal integration of previously scattered powers under the aegis of the ruler, and the external demarcation of territory over against other, foreign states.

Between states, borders had to be established. Within states, the traditional rights of nobles, clergy, peasants and local associations were suppressed as power was centralised in the ruler. Both processes were violent. According to Charles Tilly,

War made the state, and the state made war.

Building a state depended on the ability to make war. The ability to make war depended in turn on the ability to extract resources from the population. According to Gabriel Ardan’s research,

in the period of European state building, the most serious precipitant to violence, and the greatest spur to the growth of the state, was the attempt to collect taxes from an unwilling populace.

Cavanagh therefore argues that the rise of the nation state, far from being the solution to the violence, was its cause.

Uses of the myth

So the ‘wars of religion’ were not fought by Catholics and Protestants disagreeing about Christian doctrine. they were

wars fought by state-building elites for the purpose of consolidating their power over the church and other rivals.

The myth is, historically, false. Nevertheless it continues to play a central part in western society’s secular self-understanding:

In domestic politics, it serves to marginalize certain types of discourse labeled religious, while promoting the idea that the unity of the nation-state saves us from the divisiveness of religion. In foreign policy, the myth of religious violence helps to reinforce and justify Western attitudes and policies toward the non-Western world, especially Muslims, whose primary point of difference with the West is their stubborn refusal to tame religious passions in the public sphere. We claim to have learned the sobering lessons of religious warfare, while they have not. The myth of religious violence reinforces a reassuring dichotomy between their violence—which is absolutist, divisive, and irrational—and our violence, which is modest, unitive, and rational.

Why it fails

It is easy to show that the myth fails as history. But it also fails as moral narrative. Dividing the world up into nation states and granting the government of each one a monopoly on violence has not at all reduced the incidence of wars.

On the contrary it makes international disputes impossible to resolve. Should Catalonia be part of Spain or independent of it? Should Donbas be part of Ukraine or Russia? Should Ukraine exist at all as an independent country? Or, for that matter, Russia? Or any other country?

As soon as we start asking these questions it becomes obvious that they cannot be answered. Every nation state is the product of some past warlord winning a war. That’s all. Power triumphed. With very few exceptions, every border between one state and another was established at the end of a war. That’s the only reason why it has been fixed there rather than somewhere else.

Nineteenth-century racists could imagine the world’s population divided into discrete races, each of which should have its own government. We now know this isn’t true. We are all mongrels. If in doubt, get your DNA tested. There is no racial basis for dividing us up into separate nations.

So what is left? The theory that the world ought to be divided up into nation states is nothing but capitulation to the warlords of the past. Far from resolving the problem of wars, it establishes them as the only way to resolve international disagreements. To say Donbas should be part of Ukraine because that’s what it was before Russia invaded, is to say might was right last time round. This is hardly an endorsement of Zelenskiy’s case! If anything it implies that there will have to be a next time round.

Today’s concept of ‘religion’ was invented by secularists as something to be kept at arm’s length on the ground that it causes violence. Actually, people become violent over whatever matters most to them.

And, as always, young men fight in wars because powerful old men, safe in their government offices, gain power and money by causing them. And tell the rest of us that the cause is just. The myths come and go, but the flaws in human nature are still there.

1 Comment

[…] by religious disagreements, and were brought to an end by the rise of nation states. My earlier post describes his argument that the rise of nation states caused the wars rather than ending […]