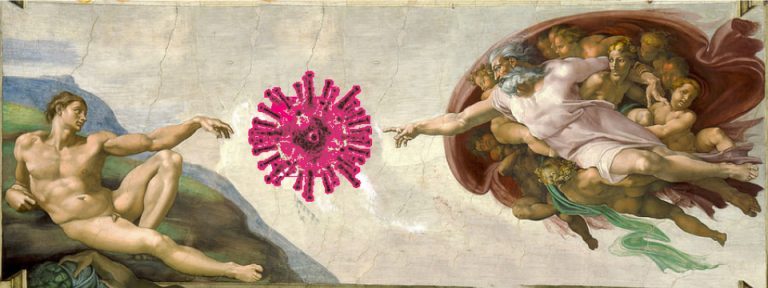

God is to be found in the virus

April 4, 2020

Coronavirus and God

April 10, 2020I am half expecting a Royal Visit. One of the peculiarities in being the Dean of Christ Church Oxford is having to reside in the Deanery, which is one of several houses that the monarchy lists on its website as an “unoccupied royal palace”. Pleasant though the Deanery is, it is not really big enough to host all our family, and then the rather larger family of Her Majesty.

Nonetheless, how did I come to be appointed by the Queen, yet at the same time be a classed as a “squatter” in one of her lodgings? The answer goes back to Charles I, who decamped to Oxford when London was hit by one of its periodic bouts of plague in 1625. Charles I lived at the Deanery for a lengthier period when evicted from London by Parliamentarians in 1642. And Charles II lived at the Deanery during the Great Plague of London. What the royal family occupy, they often claim for their own.

In 1625, Charles I had planned a rather lavish wedding to Queen Henrietta, scheduled for Westminster Abbey. But she refused to travel to our plague-ridden city. So courtiers married them “remotely” by proxy-contract in Paris. Henrietta came to Oxford, and slummed it at Merton College, while Charles and his entourage were a few doors up the road, enjoying the fine environs of Christ Church. Though they were now a married couple, they had not really been formally introduced. So a gate was cut into Corpus Christi College, allowing chaperones to oversee Charles and Henrietta, and allow them some quality courting-time.

Every year, in June, on their wedding anniversary, we unlock the gate (now at the east end of our cathedral), and toast the happy couple. They were indeed happy. The marriage lasted until 1649. Charles and Henrietta set a good precedent for royal marriages that are arranged and contracted remotely, as theirs did rather better than the founder of the modern Christ Church, one Henry VIII.

The Church of England is a denomination that is in a league of its own. You already know that. Perhaps none more so when it comes to the practise of “social distancing”, which the Church of England has been doing with effortless ease for almost four hundred years. After all, what else is a Sunday Morning 8am Book of Common Prayer Eucharist if it is not that? Minimal eye contact with your neighbour; sit at the back of the church and apart from others, ideally in your own designated pew, despite there being plenty of room at the front. No exchange of the peace or any other awkward gestures or unnecessary physical proximity are required. A nod to the priest when you leave, perhaps. Ideally no handshake, lest one is corralled into a rota for the coffee or mowing the churchyard. As a nation, some of us have been practicing social distancing since 1662. This is but a small part of our prescient English brilliance: consecrating social distancing at the beginning of every week.

Our sons (24 and 27) are currently living with us, with London in lockdown. The Deanery is slightly bigger than their two-bedroomed flat in Crystal Palace. Now they are both here with us, they help to keep us sane. They are also rather good cooks, and since leaving home some years ago, appear to have developed unusual habits such as cleaning kitchen floors, emptying dishwashers, and generally keeping spaces tidy and clean. These are tutorial tasks I long supposed that we had failed in, but our sons’ reappearance has reminded me that the enduring value of a good education cannot be taken for granted. Just because there is no sign that your students or offspring ever once listened to a word you said, you can suddenly discover that the message got home after all.

Despite lockdowns and social isolation, vibrant community networks everywhere have sprung into action. They were there all the time, like dormant bulbs waiting for a bit of sunshine and rain. And it is a crisis that often brings out the best in people. A lengthy Skype call with the Lord Lieutenant for Oxford last week revealed a common pattern: empty diaries, but never busier. The amount of coordination going on in our local communities is substantial – small acts of attentive kindness that are organised and focussed. In this county, initiatives range from contacting the elderly and vulnerable, to making sure that food and medicine get delivered. As one older member of the Cathedral congregation remarked on the ‘phone the other day, they have never been so alone, and yet in such good company. Sometimes, the virtual is better and more real than reality itself.

I continue to say my prayers each day, as clergy in the Church of England are required to do. At times like this, it is both a duty and a joy. Prayer requests are sent to me as attachments by Edmund, our Cathedral Sub-Dean. I take them on the iPad through the Alice Gate in the Deanery, which leads directly into the Cathedral. This vast space is now functioning as my temporary private Chapel. No-one else is there. I sit at my stall facing the Shrine of St. Frideswide at 7.15am, offering the prayers of the people. At 6pm, my Canon colleagues join me remotely – and we say prayers together using Zoom. I marvel at our capacity to be connected and collegial, even when we are apart. As grain was once scattered on the hillside, so we are gathered together, every day, into one body.

So, spare a thought for our dog, Lyra. A German Shorthaired Pointer, she normally makes new friends every day on Christ Church meadows. But few are out and about at present, and the early morning jog she accompanies me on each day before Morning Prayer offers no other dog-walkers to hob-nob with. There are no spandex-clad students either (not always a good look, by the way), rowing rhythmically up the Cherwell with their steady strokes. I miss the company of our students, and their cheery greetings as the morning mist ascends from the river.

That said, the deer are out and about in force, and the swans, geese and ducks are strutting about, puzzling over the vanished tourists who usually nourished them with endless supplies of sandwich crumbs to squabble over. But I remember it is spring. Life will return, and the wildlife will retreat back into the woodlands. Yet the peace of the meadows will still be there – a space for all to enjoy.

So what do we look forward to? The ‘The Gate of the Year’ is the popular name given to a poem penned by Minnie Louise Haskins. The title given to it by the author was “God Knows”. She studied and then taught at the London School of Economics in the first half of the twentieth century. The poem was published in 1908 as part of a collection titled The Desert. It caught the public attention and popular imagination when the then–Princess Elizabeth handed a copy to her father, King George VI, and he quoted it in his 1939 broadcast to the British Empire.

The poem was widely acclaimed as inspirational, reaching its first mass audience in the early days of the Second World War. Its words remained a source of comfort to the Queen for the rest of her life, and she had its words engraved on stone plaques and fixed to the gates of the King George VI Memorial Chapel at Windsor Castle, where the King was interred. You may know these lines:

And I said to the man who stood at the gate of the year:

“Give me a light that I may tread safely into the unknown.”

And he replied:

“Go out into the darkness and put your hand into the Hand of God.

That shall be to you better than light and safer than a known way.”

So I went forth, and finding the Hand of God, trod gladly into the night.

And He led me towards the hills and the breaking of day in the lone East.

We may not be able to go out much at present, but it is reassuring to know that in these times, the touching light and hand of God is with us.

So what of Holy Week this year, and the presence of God in our lives, as we continue to journey? The Gospel of John suggest sthat one of the key words or ideas to help us understand the ministry of Jesus is that of ‘abiding’. The word is linked to another English word, ‘abode’. God abides with us. Christ bids us to abide in him, and he will abide in use. He bids us to make our home with him, as he has made his home with us. And central to the notion of an abode is the concept of abiding.

To abide means to ‘wait patiently with’. God has abided with us. He came to us in ordinary life, and he has sat with us, eaten with us, walked with us, and lived amongst us. And died like us. In fact, died desolate and alone. (All but a few kept their social distance from Jesus at the cross). Perhaps that is why John ends his gospel with Jesus doing ordinary close, social-sharing activities. Breaking bread with strangers; walking on a dusty road with two puzzled disciples, grieving; eating breakfast on the seashore. God continues to dwell with us. He was with us the beginning; and he is with us at the end. He will not leave us.

God is Emmanuel – God is with us. He made us for company with each other, and for eternal company with him. God is with us in creation; in redemption, and finally, in heaven. God with us is how John’s Prologue begins – the Word was with God; he was with us in the beginning. God is with us in the valley of the shadow of death; he is with us in light and dark, chaos and order; pain and passion. And though we may turn aside from him, he will not turn from us. And in the resurrection, Jesus is again, with us – more powerfully and intensely than ever. God is with us. God is with us where we are, right now. When you think you are just hanging one. When all seems dark and hopeless. There is a light.

This is will be a Good Friday like no other. Yet though we may be socially distant from one another. But we are not apart. We are bonded together in faith, hope and love. We are bonded together in an act of recollection and remembering, where we turn back to the Servant King – the One Who Reigns from the Tree – and who bids us not to be melancholy, or even nostalgic. But rather, to re-member this world of Christ’s, as God would put it back together. That is, knitted together in acts of charity, love, service and sacrifice. Christ, in you, is the touching place between our humanity and society, and God’s abundant grace and divinity. So remember this. Jesus loves us all enough to come close to us. So close, in fact, that he will wash away all the mess, dust and dirt with water, some cloths and a towel. He holds our feet. He holds you. You can’t wash someone’s feet at a distance; you have to touch them. Frankly, there is no social distance in this. And there is no social distance between anyone and Jesus. He has drawn near.

In this extraordinary and moving poem by John O’Donohue, he offers a sense of the right kind of hopeful remembering in Holy Week – not for what once was, but for what might and shall be, if we dare to live in hope:

This is the time to be slow,

Lie low to the wall

Until the bitter weather passes.

Try, as best you can, not to let

The wire brush of doubt

Scrape from your heart

All sense of yourself

And your hesitant light.

If you remain generous,

Time will come good;

And you will find your feet

Again on fresh pastures of promise,

Where the air will be kind

And blushed with beginning

May God bless you, and keep you and watch over all those who are close to you this Holy Week. We will watch and wait in the darkness that lies before us. But also for the dawn that is to come, when the Risen Jesus will Easter in us once again.

The Very Revd. Professor Martyn Percy is Dean of Christ Church, Oxford