From Creon to Putin “That Creon – He’s Putin Personified, Isn’t He?”

May 30, 2022

Leadership And The Monarchy

June 6, 2022This post is a reflection on some of the issues raised by last week’s conference on ‘Information and Reality’ organised by the Science and Religion Forum.

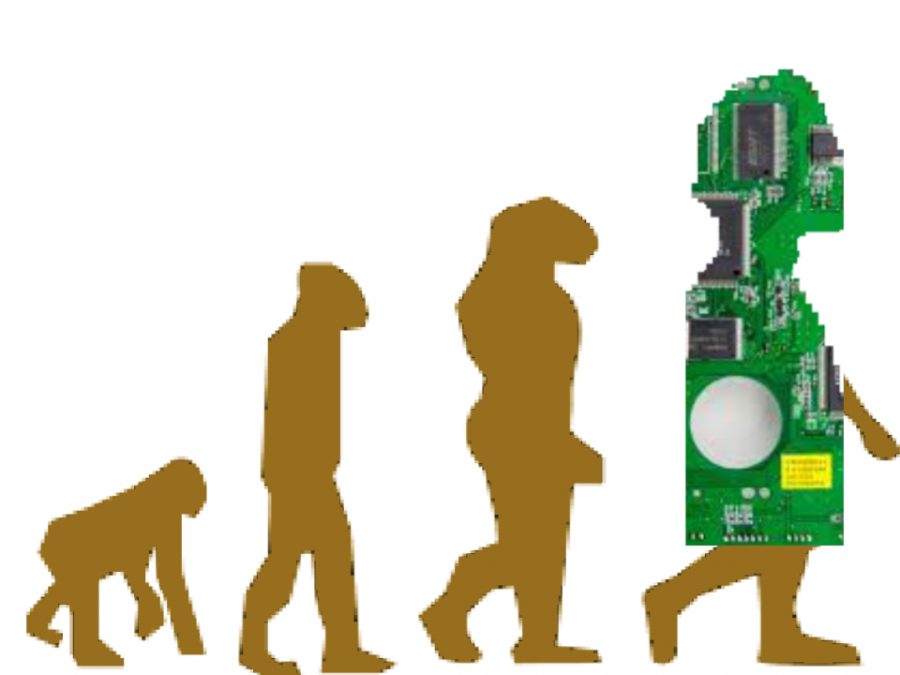

I learned a lot. You can choose: there is plenty to get enthusiastic about and plenty to be terrified by. Are new technologies taking us all into a transhuman future, more information than physical matter? Artificial intelligence and big data provide information and disinformation. It’s so convenient to buy things and book hotel rooms online, but the price we pay is that servers somewhere in the world provide to unknown others more information about us than most of us would imagine possible.

We are targeted by messages designed specially for us, by algorithms using huge amounts of data – about our expenditure, our interests, our commitments and our moods. All this is used to guide us in whatever ways the buyers of the data choose: to get us spending money where they will profit, or voting for parties they prefer.

We are learning to live with it. When a taxi driver received a new booking through his mobile phone, he was heard to say he had been ‘blessed by the algorithm’. Others have excused themselves for their actions by saying ‘the algorithm made me do it’.

So as new information technologies ‘know’ ever-increasing amounts about us, are we creating new gods out of them? Are we treating them as humanity’s guides into the future?

I shall focus on a short paper by Michael Burdett and King Ho Leung, who described the issue in terms of transhumanism. I’m still not sure I understand it, but it’s about the significance all this mass information has for – as they put it – ‘how we understand just about everything today.’

It is now scientifically respectable to say that the basic constituents of the universe are not matter, as previously thought, but information. So: at some stage in our ultra-technological future, will we be able to dispense with our bodies?

What the speakers were concerned about was the way the world of transhumanist theory holds to an ideology that ‘exhibits gnostic and docetic religious overtones’. While that discourse claims to reject the supernatural,

their actual practices… posit the infosphere as a kind of supernatural realm that is often set in opposition to the natural or physical world.

Hence the analogy with Gnosticism and Docetism. Transhumanists can represent us

as divine sparks trapped in the physical world which, when manipulated properly, can lead to the transcendence and apotheosis of the subject into the pure infosphere.

The boys with their toys

Of course every new technology generates its enthusiasts, proclaiming that life is henceforth going to be a lot better because of it. Many do indeed help at least some people. I am typing this into a laptop while wearing spectacles, and wouldn’t have been able to otherwise. But many technologies benefit those who control them at the expense of those who don’t. Since the ‘big data’ are controlled by a small number of ultra-rich people who use it to generate yet more money for themselves, I find it difficult to see why we should expect the overall results to be desirable for anyone else.

Anyway, why would we want to dispense with our bodies? There is a long history of techno-enthusiasts telling us the latest new innovation will enable us to dispense with something the rest of us would rather keep. I am reminded of those earlier theories that world hunger could be eradicated by manufacturing vast quantities of some nutritionally adequate substance to give to the hungry. Those who supported the idea never wanted to restrict their own diet to that substance, of course. Others have looked forward to the day when all babies can be produced in artificial ways, so we can dispense with sex. Maybe some would like that, but most of us wouldn’t. Enthusiasms of this type always seem rather disconnected from the question of what problems really need solving.

Hope and determinism

Despite the fact that those speakers are a lot younger than me, I do wonder whether there is a generation thing here. At any rate, in my lifetime we seem to have passed through three stages of expectation about the future.

Can-do

The first was the can-do one. I was born in 1948, which some say is the best year ever to have been born. The reason is the welfare state. After the disaster of the Second World War the public mood was determined to make life better for everyone. We were going to make it happen by means of our political structures. Health services for everyone, houses for all families and schools for all children were created to make direct provision for what people needed. We, the public, were responsible for making it happen.

Leave it to the experts

Later it was transformed into something else. Harold Wilson’s 1963 speech about ‘the white heat of technology’ can be seen as a watershed. It gave the British public the sense that people’s lives would continue to get better, but for a different reason. Instead of direct provision to meet needs, needs would be met by new technologies.

But new technologies are not produced by the political process, let alone by the values of the general public. They are produced by experts, each in their own expertise. The general public, therefore, could withdraw from responsibility, still hopeful about a better future for everyone, but no longer responsible for doing anything about it. We could leave it to the experts. It would just happen.

Trusting technology like this is, in effect, treating it like a god who knows what we need. Indeed, the 1960s were the high point for popular atheism, so perhaps it is not surprising that public sentiment found a replacement divinity for us all to trust.

Can’t-do

But we don’t sing hymns or say prayers to technology. New technologies have harmful as well as helpful effects, as is well known to Ukrainians whose home town has been destroyed by high-tech bombers.

One of the things that came across clearly at the conference was that the proponents of Big Data and associated technologies often treat it as inevitable. As the disadvantages become clear, enthusiasm for an exciting future appeals to, and gradually turns into, resignation. However we feel about these changes, they are coming and we will just have to learn to live with them.

So by subcontracting our hopes to technology we have left the future of our lives, and the lives of our children, to be decided by technological experts – or rather, the billionaires who employ them. Such people are rarely the best decision-makers.

Three responses

So here are three ways we can respond to all this new technology. Either it’s up to us, collectively, through our political processes to think through what will help and what won’t; or all will be well if we leave it to the experts; or, sadly, we have no choice but to leave it to the experts.

Our speakers were right to compare this third group with Gnostics. Ancient Gnostics despised physical bodies and longed for the day when the divine spark within them would escape this evil world to re-unite with their true heavenly home. The Gnostics of today believe that with new technologies we can escape the physical world we are trapped in and become part of a new transcendent infosphere.

The Early Catholic Christians like Irenaeus opposed the Gnostics of their day because they believed the world was a good creation by a good god. The correct response to the state of the world was not to escape from it but to celebrate it, give thanks for it and treat it the way its creator intended.

So it is today. The world, as it has been given to us, allows us to do many things. Some are more constructive than others. To provide the best possible future for ourselves and our children, the task facing us is moral, not technical: to make sure everyone has what they need so that everyone can celebrate the world’s goodness.