Roe v. Wade – What Would Jesus Do?

May 7, 2022

Elaine Graham: What are we doing when we talk about God? Modern Theology and the Crisis of Faith

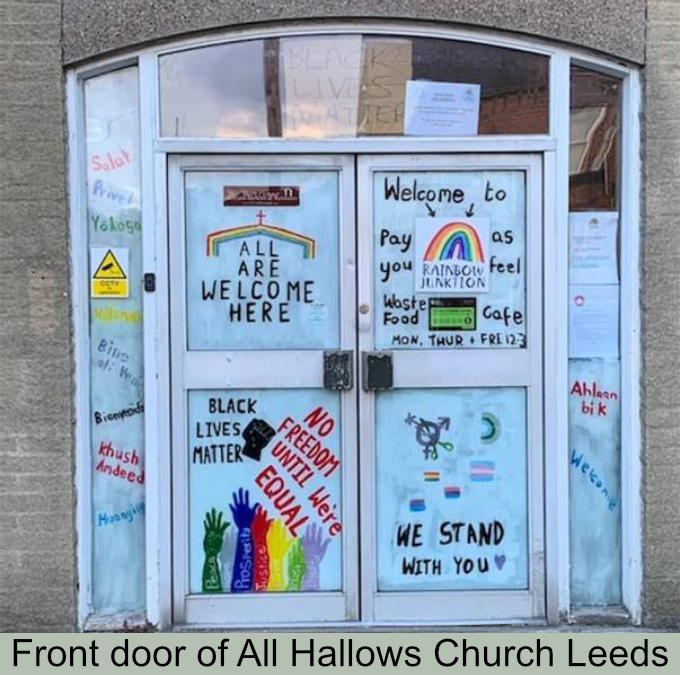

May 17, 2022The service at All Hallows Leeds yesterday was run by its group supporting refugees. We were told about the Home Office’s regulations and how we can help; but what had us in tears were the first-hand accounts by two people who had gone through the process.

I won’t give personal details. Apart from anything else the safety of family members demands anonymity. Other websites describe what refugees have to go through. Suffice it to say that we were all horrified that our own British Government could treat anybody at all with such cruelty.

But it does, and we the British people voted for it. Rather than simply lament the callousness to which our rulers have descended, let’s ask how British culture descended to the point where we chose to elect people like that, and how we could do better in future.

I was a baby boomer. I have vague childhood memories of talk about Second World War refugees. Some countries took them in more willingly than others. We disapproved of the nasty countries that didn’t take their share. And now Britain is one of the nastiest. Why?

After the Second World War there was an international movement determined to create a better world order for everyone. Internationally, institutions like United Nations were set up. Nationally, governments set up distribution systems like Britain’s Welfare State, designed to ensure that everybody had the basic requirements of a decent life.

Providing for other people costs money, and governments took it from the richest. Rich people don’t like that. Being rich brings the desire to become even richer. And it also brings power.

Gradually the redistribution systems have been whittled away. Governments and their supporters have encouraged us to stop expecting everybody’s needs to be met.

A major step was to revive the 200-year-old theory of Thomas Malthus that shortage is inevitable. To meet everyone’s needs, we need an ever-growing economy. It’s not true, and in Malthus’ day it was widely condemned as unchristian; but it’s an excuse for not caring about the destitute.

This paved the way to a change of moral philosophy. As a son of a vicarage, it was central to my Christian upbringing that practical decisions should be guided by the general principle of caring for other people. I have lived through, and often wondered about, the change to a different general principle: that the well-being of the economy should be our moral guide. Providing for people’s needs should then, in theory, be an indirect result of a healthy economy.

Of course it never was. But once this myth had entered the mainstream of public discourse, it then became possible to judge people according to their economic impact. Some contribute more to the economy than they take. Others are a drain on it. Refugees, perceived as a drain on the economy, can then be treated as a threat to the British people.

This, of course, is neither economically nor ethically serious analysis. It’s political rhetoric. Governments demonise

Every government wants something or somebody to demonise. Otherwise it is to blame for all that is wrong.

As the poor get poorer, they notice how government claims about the economy don’t match their own experience. Why is their standard of life constantly declining? Why have they become dependent on food banks? If it isn’t the Government’s fault, whose fault is it?

There is usually some unpopular minority they can pick on. The Irish, Pakistanis, Ugandan Asians, gays, people on benefits and many others have taken their turn to be demonised.

Refugees are an extreme case. If you have been hoodwinked into believing that your poverty is caused by people on benefits, you may actually meet someone on benefits and learn about their situation. That may change your understanding. But you aren’t going to meet someone who hasn’t been allowed into your country. The plan to deport refugees to Rwanda has received a well-deserved outcry, but so far the Government hasn’t proposed it for anyone else.

Ethical dilemma?

So how does the Government defend its cruelties? It has a way of doing so, and here I must confess my view that the rise of atheism has made it possible.

To justify a moral claim we need some kind of moral philosophy. Most of us never think about our moral philosophies. We just presuppose them.

One is that the world has been designed in such a way that the best way to live is to care for each other, and make sure everybody has what they need for a fulfilling life. Historically, Britain has inherited it through centuries of Christianity.

It presupposes that the world has been intentionally designed to work well in this way. There must be some kind of designer with moral authority.

An alternative moral philosophy is that the world is not intentionally designed at all. No mind planned our evolution. Deciding what to do about refugees is, like every moral discourse, an activity restricted to humans. Since no other beings can create values, all our values are what we humans create.

So who are the ‘we’ who create British values? Each of us equally? Only on a very limited, personal level. On public matters the ‘we’ who create the values of British society are of course its ruling classes and their spokespeople. Billionaires own nearly all our newspapers. Even the BBC has to bend over backwards not to offend the Government in case its funding gets cut.

According to this moral philosophy, there are no moral authorities that transcend the Government. It follows that the Government’s values must be right by definition. Families are to be split up. To Rwanda some of them must go. Why? Because the supreme moral authority, i.e. the Government, says so.

I’ve never come across anyone who believes this consistently. Even the most convinced atheist can denounce our hostile environment as strongly as any traditional Christian. Even the most ardent supporter of Priti Patel doesn’t think her views are necessarily correct. In practice, therefore, the dominant public discourse, with its techniques for demonising minorities, doesn’t describe our values at all.

The overwhelming majority of us never think through our moral philosophy. But whether we are Christians or Buddhists or atheists or ‘no religion’ we all have a sense that some things are wrong, and may be wrong even when governments declare them right.

Faced with horrors like the way refugees and asylum seekers are being treated, most people respond as though there really is a moral authority competent to tell the Government and its spokespeople that what they are doing is wrong. I would add that they are right to do so.