Refugees and the hostile environment

May 16, 2022

Mikhail Khodarenok – The ‘What If?’ Question

May 19, 2022We are grateful to Prof Elaine Graham FBA for providing Modern Church with this transcript of her final lecture as Canon Theologian of Chester Cathedral, given in the cathedral on May 10 2022

I should begin by defining what I mean by my title: What are we doing when we ‘talk about God’? And what do I mean by the ‘crisis of faith’?

In this lecture I want to trace how Christian theology has responded to some of the most significant social, economic and intellectual movements that have shaped human history over the past 200-300 years. In the process, we will encounter the question of whether these developments represent a legitimate response to changing times and circumstances – of seeing the Spirit of God at work in the world beyond the church and in sources of human wisdom beyond the received tradition – or whether it represents a capitulation to secular or non-Christian world-views and a departure from proper orthodoxy and the strictures of tradition.

You may not be surprised to hear that I will argue that the ways we talk and think – even speak to – God are never immune to historical events and changing times. My argument is that theology as ‘talk about God’ is always a conversation between tradition and experience; between the authority of the past, enshrined in the sources of Scripture, doctrine and Church practice, and the imperatives of the age.

The modern era represents exceptional transformations in human history, characterised by constant change and innovation. What we think of as our contemporary world has its roots in a number of significant developments that date from the late C17th through to the C19th. These include the rise of a particular scientific method based not on divine or Biblical revelation but on observation and experiment; the emergence of a discourse of human sovereignty and self-determination; forms of liberal, participatory democracy founded on the will of the people rather than divine right of rulers; the spread of capitalism, the supremacy of market economics and the profit motive; and the beginnings of the European conquest of large parts of the non-Western world.

At various points in the lecture I will pause to introduce what I have called “Interludes”. These serve to illustrate what I am saying, often through the voice of a historical or contemporary source. I will try to keep my analysis of these to a minimum, but hope that they will excite further comment and discussion later.

THEOLOGY

When we refer to theology, we normally mean the attempt to arrive at a systematic account of God and of God’s relations with the world. Traditionally, Christians have understood their knowledge and their language about God as coming from several sources. The first and primary form is that of revelation – Scripture, or sacred texts. For some, this represents the voice of God speaking directly into human consciousness; but others would argue that while such sources still reveal definitive knowledge, this revelation is always mediated through human language and culture and conditioned by historical circumstances.

The second source for theology is the believing community, as the trustee of a living tradition of doctrine and practice. The term “tradition” describes the way in which the community develops an interpretation of Scripture over time. But once again, Christians would vary as to whether tradition is fixed and authoritative for all times, or whether it evolves and is open to criticism and revision.

The third source for theology is “reason.” Knowledge and talk about God are not simply grounded in claims to “authority” independent of human reception and interpretation. In some theological traditions, the insights of human culture, of science, the creative energies of the arts, as well as our apprehension of the natural world around us – in other words, sources beyond the strictly ‘theological’ or religious — are legitimate and essential sources for how we think about the nature of God.

The last traditional source for systematic theology is “experience,” by which is meant personal or collective experience of God. For some theologians, subjective experience is the core of religion. It is something that is often seen as grounded in the affections rather than cognitive understanding. Certain types of modern theology have argued that the corporate experience of the people of God, especially those who are oppressed, is important in making sure that our theological understanding of the world takes the issue of justice seriously. So talk about ‘experience’ immediately begs the question of whose experience are we talking about.

We have, then, four primary sources of theology: Scripture, tradition, reason, and experience. The four are woven together differently from tradition to tradition. We’ll see how they come into play in modern theology as we go along.

‘MODERNITY’

What does it mean to be modern? When did that age begin? And what were the catalysts that sparked the formation of the world we take for granted in C21st Europe and which arguably have had a fundamental effect on the way we think, talk and speak about God?

We could summarise ‘modernity’ as entailing any or all of three clusters of meaning:

- An historical period from the European Protestant Reformation (C16th) through to early C20th.

- A set of social, intellectual and economic transformations: industrialisation; democracy; science and technology. With that, far-reaching critiques of religion, including atheism, religious pluralism, secularism – what some would term ‘the death of God’.

- A set of ideas or values: humanism (emancipation, agency, self-sufficiency), reason, progress, free enquiry; division between public and private. Modernity was the ‘age of big ideas’, -isms and -ologies.

Science, Religion and Faith

A good way to conceptualise the radical disjuncture between the modern world and its ancient and medieval predecessors is to start at the level of world-view in the most concrete sense of the term: the picture of the world that every age carries in its imagination, and which functions as a means of physical, psychological, and religious orientation.

Interlude: The universe according to the ancients

In the ancient Greek world-view the earth was located in the centre of a finite universe and enclosed within the concentric spherical shells of the known planets, which were in turn enclosed by the sphere of the fixed stars. The sun, moon, planets and stars were believed to all revolve around the earth.

From Plato and Aristotle on, a sharp distinction was made between the heavens, the realm of perfection and harmony, and the “sublunary” region including the earth, characterised by corruption and change. This heaven, the abode of angels and saints, was counterposed to its opposite, hell, located in the centre of the earth at the point of farthest remove from God.

This view survived until the time of Nicolas Copernicus (1473-1543 CE) who first posited a model of the earth revolving around the sun, not the other way around. Historians and philosophers have long associated this “Copernican Revolution” (the label was coined by the modern philosopher Immanuel Kant) with the origins of modernity and its break with the past.

The full impact of this change was brought home in the work of Galileo (1564–1642). Using the new-fangled technology of the telescope, he was able to produce actual evidence for the heliocentric theory. It is surely no accident that the most notorious clash between the official church and modern science was occasioned by Galileo’s discoveries, which brought into stark contrast the incompatible paradigms of the old world picture and the new.

The new science reached its culmination in the work of a man born the same year that Galileo died, Isaac Newton (1642–1727), whose Principia Mathematica first exhibited the new world-view in all its glory. He portrayed the universe as a vast cosmic machine in which space and time are the infinite and uniform containers of material bodies, which move according to universal laws. God had originally set the universe in motion and now intervened only occasionally in order to make minor adjustments to the mechanism, which was developed into the “watchmaker” God of the Deists.

There is ambivalence, however, at the heart of this modern cosmology. On the one hand, it represented the displacement of humanity and planet Earth from the centre of the universe. We are part of an infinite galaxy of stars and planets, which predates the emergence of human beings by billions of years. On the other hand, this new model of the universe has been discovered by human reason, in the form of scientific investigation, so that in a different and more important sense, humanity and human agency is more than ever at the centre of things. If you like, the old geocentric world has been replaced by the modern anthropocentric world.

Whether we are aware of it or not, these dimensions of ‘modernity’ have irrevocably shaped the way we ‘speak of God’ or do our theology. Modern science stresses that nature operates according to universal laws or principles; and that nature can be investigated and manipulated through systematic observation and experimentation according to these laws. However, in the light of science and our understanding of the universe after Copernicus. there is a real sense in which we cannot believe many doctrines in the same way our forbears did. To take one example, the doctrine of the Ascension in a three-tier universe involves Jesus’ “ascending” into a heaven above the clouds. In a post-Copernican universe this notion of heaven is not an option.

There were political parallels as well, represented most clearly by the ‘democratic revolutions’ of the late C18th which saw popular uprisings by the American colonists against the British monarchy and the establishment of a secular republic in France. Political authority was understood to rest in the will of the people and not in divine right or fiat: freedom from autocratic rule, and the rights of self-determination, were seen as the key to Enlightenment and progress. And the Church found itself associated with the forces of conservatism, stressing obedience to ecclesiastical and monarchical authority rather than the quest for freedom and self-determination. It would not be the last time that theology and church teaching was perceived as a block on liberty.

This equation of truth with the empirical findings of modern science and history undercut the claim to truth asserted by traditional religious (read Christian) authorities. Though not without resistance from religion, modern culture separated the secular from the sacred and faith from reason.

In part, this was as a consequence of the religious wars in Europe in the C16th and C17th, in which Catholic and Protestant factions and nations, marching under the banners of competing religious absolutes, wreaked havoc over much of Europe. One of the legacies of one conflict, the Thirty Years War (1618–1648) was the so-called Westphalian Settlement that put an end to the wars of religion, signalling a separation of Church and State and between politics and religion. Faith was consigned primarily to the arena of private belief rather than public practice and profession or government coercion.

This turn to religion as an aspect of personal choice and private subjectivity was further engendered by modern philosophy after Immanuel Kant (1724–1804). He drew a strong distinction between the ‘facts’ of the external world and the interpretation of experience in human consciousness. He challenged the idea that the human mind sim- ply passively receives sense information from objects external to the mind. Rather, he argued that knowledge of the phenomena that appear to our senses is subject to in- terpretation and mediated to us through language and culture. So already we have an understanding that there is no ‘pure’ revelation independent of our active conscious- ness. It follows that whatever the external world consists of, it is only available to us via our own processes of interpretation. Any concept of ‘revelation’ is never unmediated or absolute.

Kant also argued that the test of any knowledge rests in practical reason, or how well it fulfils our sense of moral obligation. As we’ll see, that opens the doors for modern theology to conceive itself a a form of ‘practical wisdom’: the test of authentic theology lies in its moral impact, its practical efficacy, in terms of what kind of human lives, what kind of world, it engenders.

In the face of scientific questioning of literal interpretations of creation from Genesis and the growing use of scientific method to challenge historicity of Bible, miracles, the German theologian Friedrich Schleiermacher also took a subjective turn, towards human feeling and consciousness as constituting the heart of religion. The roots of faith rest in a sense of “absolute [or utter] dependence” on a transcendent other; a religious sensibility that, argued Schleiermacher, is a human universal. This spiritual intuition is available to every human being; but in sharp contrast to the natural religion of the Enlightenment and to Kant’s ethical religion, it is located in neither the intellect nor the will but in the affections. This view is often associated with the Christian tradition of Pietism. God is revealed through the workings of the human heart and emotion and religious conviction is grounded in personal experience of a direct relationship with the divine – think, for example, of John Wesley’s account of feeling his ‘heart strangely warmed’ as the source of his assurance of faith and salvation.

Interlude: A vindication of the rights (and reason) of women (1792)

“Children, I grant, should be innocent; but when the epithet is applied to men, or women, it is but a civil term for weakness. For if it be allowed that women were destined by Providence to acquire human virtues, and by the exercise of their understandings, that stability of character which is the firmest ground to rest our future hopes upon, they must be permitted to turn to the fountain of light, and not forced to shape their course by the twinkling of a mere satellite …

Consequently, the most perfect education, in my opinion, is such an exercise of the understanding as is best calculated to strengthen the body and form the heart … In fact, it is a farce to call any being virtuous whose virtues do not result from the exercise of its own reason. This was Rousseau’s opinion respecting men; I extend it to women, and confidently assert that they have been drawn out of their sphere by false refinement, and not by an endeavour to acquire masculine qualities.”

Mary Wollstonecraft, A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, 1792

The French revolutionaries and philosophers of the Enlightenment and the American Fathers of the Revolution laid great store on the capacity of human beings to shape their own destinies free of the constraints of tradition, autocracy, superstition and dogma. But arguably, this was still a partial vision. It is unlikely that these Men of Enlightenment would have extended those rights and privileges to their wives, daughters, or servants and certainly not to the African slaves who maintained their plantations. So this vision of universal humanism is flawed – and gradually modern thought, including theology, has had to come to terms with that.

One of the first representatives of that protest is the early feminist Mary Wollstonecraft in her work, A Vindication of the Rights of Women. On what grounds, she asks, are these much-prized faculties and attributes of rationality and self-determination to be withheld from the female of the species? She mocks a stereotypical model of femininity but argues that women cannot be denied their claim to full humanity alongside men. If the exercise of reason is the key to achieving one’s full potential, she argues, then there are no grounds not to extend this right to women as much as men.

Key Themes: Summary

So in summary: the ethos of Western modernity can be summarised in terms of the principles of freedom, revolution, reason and criticism. These called for people to think and act for themselves, free from immature or subservient deference to the dogmas of Church or diktats of the State. Reason was the key to progress and human emancipa- tion; every aspect of social, political and religious life should be subject to rigorous examination and critique. It was also strongly ‘humanist’ in that human judgement and rational exercise of will, rather than biblical revelation or ecclesiastical authority, was the ultimate moral arbiter.

THEOLOGY IN THE FACE OF MODERNITY I

This is the backdrop against which theology and the churches have done their work and practised their faith.

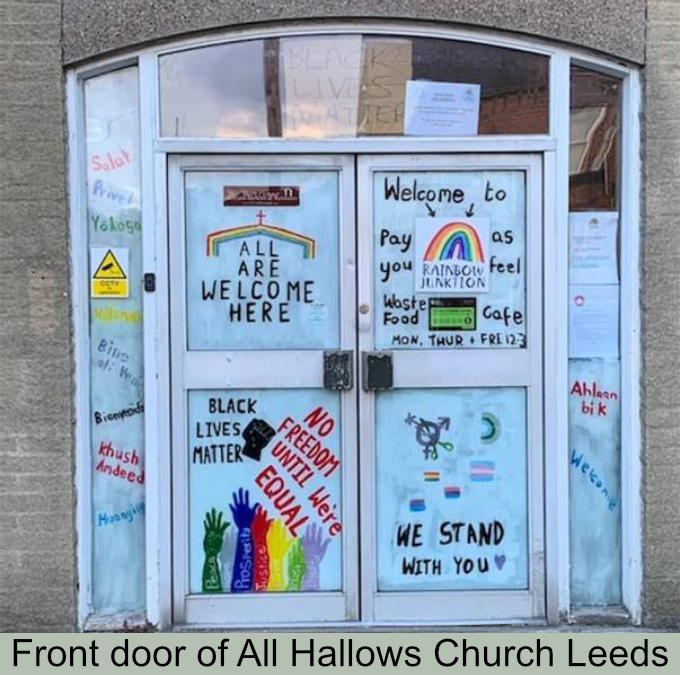

One highly influential version of the theological responses to modernity appeared in the various politically focused theological movements from the 1960s onward: Liberation Theology, first in Latin America and later elsewhere; also Black, Womanist and post- colonial Theology; and Feminist Theologies of several kinds. It’s interesting to note how these movements returned to those four sources of theological understanding in the light of the new climate of modernity, revolution and science.

So, ancient and medieval theology had always drawn on the secular discipline of philosophy to help them understand the nature of God and the task of theology. But now, these modern theologians looked to economics, historical criticism, gender and race theory, and political philosophy as part of their analysis.

Beginning with movements in the progressive Roman Catholic churches in Latin America, theologies of liberation began to emerge which reflected modernity’s turn to the subject, to the rise of humanism and a concern with emancipation from oppressive and unjust social systems. Small groups, known as basic ecclesial communities, grew up as the focus of ‘ new way of being church’, characterised by grass-roots organising and education. In particular, these groups emphasised the importance of reading the Bible from the perspective of the poor. It was, perhaps, an extension of the Protestant Reformation which stressed the importance of making Scripture as the Word of God available to ordinary people as an essential route to salvation.

So, liberationist approaches to Scripture were read through the experiences and lives of those who have been excluded from the official canon: those on ‘the underside of history’. Similarly, history itself is transformed through the praxis (actions) of the poor. Theology, including and especially the nature of God, must be read through the eyes of the poor and economically marginalised. This served to expose false or ‘ideological’ versions of the Gospel that taught passivity in the face of injustice, or a privatised spirituality that divides material welfare from spiritual health. History is the arena of God’s action, understood as the transformation of the world through love. Theology is not primarily a philosophical exercise but a praxis of liberation, drawing on the historic witness of the prophets as its model.

Similarly, when approaching tradition, these theologies adopt a dual approach of what I would call ‘critique and reconstruction’. This is particularly clear in forms of feminist and Black theologies. They approached Scripture and tradition with ‘the hermeneutics of suspicion’: failing to see themselves reflected in the Bible or Christian doctrine, they apply that same principle of ‘God’s preferential option for the poor and excluded’. Women theologians have voiced their exclusion from worship and leadership within the Church, often linking this with the invisibility of women in the Bible and the andro- centric (or male-centred) language in which it is written. God in the Judeo-Christian tradition had so unequivocally been associated with masculine attributes and thereby sanctioned men’s subordination of women in both the church and the culture at large.

The critical task, then has been to expose the partiality of received tradition and to challenge its authority; and the reconstructive task to return to hidden and forgotten parts of tradition in order to discover a more authentic (inclusive, representative) account of the nature of God and the history of salvation.

In feminist theology, this reconstruction is measured against the rubric of ‘the full humanity of women’ as grounded in the dangerous memory of Jesus of Nazareth and his inclusive ministry. It constitutes a rebuilding of the old tradition, grounded in new ecclesial and textual practices of inclusion, attention to the marginalised, and a vision of an egalitarian community of women and men in the church. Similarly, the starting-point for Black and womanist (African-American feminist) theologies of liberation is an apprehension of the exclusion of African-American experience and the life of the Black church from the official theological canon. Received tradition is condemned for failing to reflect the historic struggle of Black and colonised peoples against slavery and discrimination, and even for providing a justification for White supremacy.

The best-known advocate of “black theology” is probably James Cone. Writing at the time of the civil rights movement in the U.S. and the rise of “Black Power”, therefore, Cone seeks to rectify the silence and invisibility of Black people by dismantling the symbols of White privilege and introducing theological and cultural sources that reflect Black lives. Like Liberation and feminist theologians, Cone begins with a strong sense of outrage at the denial of human dignity inherent in the structures and practices of racism. For him, this runs like a deep seam of injustice throughout the history of the United States: slavery, Civil War, civil rights movement and continuing inequalities affecting African Americans.

For Cone, Black theology begins with a thorough-going critical dismantling of the racist canon and heritage of Christian theology and then proceeds to its reconstruction into a tradition capable of affirming the full humanity of Black people. This entails both a reinterpretation of Christian teaching – especially Biblical literature – and a search for new well-springs of authentic Black self-expression. Specifically, Cone embarks on a retrieval of the liberative testimony of Scripture – and especially the centrality of the book of Exodus and the emancipation of Israel from slavery in Egypt; plus a rethinking of the person and work of Jesus Christ. But in addition, Cone looks to the harnessing and celebration of the folk traditions of the Black churches: oral history, art, song, pre- Christian and African spiritualities.

Interlude: New ways of naming God, being church and speaking of Christ.

Gustavo Gutierrez: ‘The question of God in Latin America will not be how to speak in a world come of age, but rather how to proclaim God as Father in a world that is inhumane. What can it mean to tell a non-person that he or she is God’s child?’ (Power of the Poor in History, 1986, p. 57).

“If God is male, then the male is God” (Mary Daly)

“We black theologians contended that if God sided with the poor and weak in biblical times, then why not today? … In the place of the white Jesus, we insisted that ‘Jesus Christ is black, baby!’ It was one thing to identify liberation as the central message of the Bible, but something else to introduce color into Christology.” (James Cone)

The task of theology is to name that sin and provide the resources by which the human condition can be transformed: a work of orthopraxy (right action) rather than orthodoxy (right belief). Mission and the work of the church is not aimed at the converting the non-believer, but assuring those rendered ‘non-persons’ by poverty or exploitation – dehumanisation – that they are indeed children of God.

The issue of inclusive language has also emerged out of the feminist movement; but it goes far beyond the simple level of whether or not to replace father-God imagery with that of Mother-language. Mary Daly’s famous adage, ‘If God is male, then the male is God’ expresses this very power of God-talk as sanctioning wider social relations. As the Jewish feminist theologian Judith Plaskow put it, “the right question is theological”: how Christians speak of and imagine God has a bearing on what kinds of human relation- ships they choose to value – language shapes and reflects our perceptions, it builds a world and fundamentally shapes our lived reality.

Was Jesus racially Black? Or is it more that James Cone is looking to link the identification of the historical Jesus with the struggles of all peoples of African descent for full personhood and agency? Cone’s declaration of the Blackness of God was an integral part of that reconstruction of theological tradition, since it becomes a way of reclaiming Black identity as made in the image of God and of locating Jesus’ solidarity with the poor and oppressed in the possibility of his incarnation as a human being of colour.

All these constitute a massive paradigm shift in theological priorities: for whom does theology speak? Who and where is God to be discovered? How do we understand the person and work of Christ? How do we conceive of the phenomena of sin and salvation? What images, cultural forms and language does theology speak? And ultimately, what is the purpose and use of theology?

THEOLOGY IN THE FACE OF MODERNITY II

One of the greatest challenges for modern theology comes from the advances of scientific knowledge, not helped by the fact that for the ordinary person in the street, it is often assumed that science and religion are incompatible. Many scholars would say it is a matter of world-view: our mental and symbolic pictures of the universe we carry around with us. Is it of the world as a machine, working to mathematical rules? Is it of nature red in tooth and claw, competing for scarce resources? Are these compatible with the views of creation we get from Scripture and tradition?

And what then does that imply for Christians who claim that God is creator of all things? How is God to be conceived in relation to the cosmos? If reality is evolu- tionary, dynamic, emergent and inter-related, how does God relate to everything that is not God? One response has been on the part of what are called process theologies and forms of ‘pan(en)theism’ which abandon hierarchical views of the universe – God dispassionate, immutable, up in heaven — in favour of a divine immanence that is not ‘above’ or ‘beyond’ the world but present throughout all of reality. God’s existence is to be understood less as Being or unchanging substance and more as an animating pro- cess that suffuses all other existence.

In rejecting ideas of divine immutability and impassibility, the arguments of process theologians converge with forms of modern Christology which stress that in the cruci- fied Jesus we see a divine identification with the world’s suffering: the Crucified God.

Where was God in Auschwitz … Rwanda, Kyiv and Mariupol?

Which connects with another challenge to face Christian theology in the modern world: that of suffering and massive human injustice. This is often stated simply as the question, ‘Where was God in Auschwitz?’ To which we might add other horrifying events of genocide and war throughout the C20th and C21st: Hiroshima, Rwanda, or even Kyiv and Mariupol. This is of course also a question of theodicy: how does a loving God permit such terrible suffering?

For some contemporary theologians, the crucifixion has assumed new relevance as a way of responding theologically to the massive scale of human suffering of the C20th. They begin with the person and work of Christ, arguing that at the very heart of Christianity is an image of torture and execution. The German theologian Jurgen Moltmann picks up Martin Luther’s assertion that ‘there is no other God for us than … the man on the cross’ – a recognition that ‘the death of God’ is the very fulcrum of Christianity.

This is Moltmann’s answer to those who cannot believe in God not so much on philosophical or scientific grounds but for reasons of morality – what he terms ‘protest atheism’. In the Cross, argues Moltmann, we see both the call to remember (anamnesis) or the refusal to forget, a commitment to continue to tell the story of suffering as a way of keeping faith with history’s victims. And the ‘dangerous memory’ of Jesus’ death be- comes the very frame through which Christians think about the world and think about God. God is not dis-passionate, impassible; but flesh and blood, present alongside the victims, sharing and entering into their suffering. A God who merely stood by would be unworthy of worship, says Moltmann, because he would have shown himself as in- capable of love. But if the Cross is the ultimate expression of divine love, then it is possible to regard the tragedy of human suffering in an entirely new light. God’s ‘solution’ to radical evil lies in the future, as revealed in the resurrection of the crucified Jesus.

By contrast, another theological response to radical evil stresses not the immanence and humanity of God but its antithesis: the very transcendence of God. Karl Barth, the C20th Swiss theologian reacted against the C19th liberal theologies that bought into those modern ideals of progress, reason and humanism. He argued that theologies which seek to accommodate themselves to human developments in culture are at risk of being unable to discern the idolatrous direction of human history. Theology, even as social critique, must stand apart from the spirit of the age. For Barth, this was catalysed by the rise of Hitler in the 1930s and the collusion by large parts of the German Protestant Church with the Nazi regime. He was part of a group that issued ‘the Barmen Declaration’ which deliberately stressed the transcendence of God, as ‘wholly Other’ to human reason and religion.

While God may be able to be described by analogy in human terms, ultimately, as humans, we are finite creatures responding to the self-revelation [the Word] of the infinite God, most notably in the person of Christ and through the Bible. True religion is always a response to that initiative that can only come from God to us. The Word of God speaks into history and is the true source of our morality, especially in situations where a political regime claims absolute loyalty over its subject. Talk of God as ‘wholly Other’, then, serves as the source of resistance to any earthly regime that attempts to assume a quasi-religious authority.

Interlude: the Suffering God

This paradox, of the immanent, suffering Christ, and the mystery of the infinite creator God, is superbly expressed for me in words by the contemporary hymn-writer Graham Kendrick.

“Come see His hands and His feet The scars that speak of sacrifice; Hands that flung stars into space To cruel nails surrendered”

(Graham Kendrick, “The Servant King”, 2001)

This is also an example of talk about God that originates in worship – and highlights for us the importance of metaphor, poetry and hymnody in speaking of God. No-one thinks this is trying to be an accurate account of the Big Bang, but it is speaking metaphorically of a creator God who is both the source of existence itself and yet also surrenders to suffering and death.

Context and Catholicity

One major driving force in modern theology is the wish to make theology relevant to the questions that human culture is asking. The theologian Paul Tillich argued that theology is inherently dialogical, with the world asking the questions (for him, mainly existential) and theology providing the answers, the key to the human condition. Yet we have the question of how to balance the specificity of our own times with fidelity to the continuity of historic tradition. What, if anything, unites these many expressions of the gospel? What prevents diversity descending into relativism? To what extent should some degree of affinity be expected, either cross-culturally or historically throughout the generations?

For many contemporary theologians, this is both a philosophical and doctrinal question – about the kind of knowledge embodied within the tradition – but also a moral, even one might say a missiological conundrum. How does the contemporary church speak of God meaningfully and credibly to each new generation when its language, its power structures, reflect a bygone age?

The Roman Catholic missiologist and contextual theologian Robert Schreiter puts it like this:

“How is a community to go about bringing to expression its own experience of Christ in its concrete situation? And how is this to be related to a tradition that is often expressed in language and concepts vastly different from anything in the current situation?” (Schreiter, 1985, p. xi)

In response to these objections Schreiter has suggested that it is possible to talk of a ‘catholicity’ of theologies which requires a comparative perspective by which particular expressions gauge their authenticity against others. First, specific expressions of theo- logical understanding should be true to the breadth of historic tradition. Second, enduring patterns of worship serve as the ‘touchstone’ of authentic identity. Third, the integrity of faith is judged by its service in pursuit of justice – a echo of the liberationist emphasis we heard about earlier. Fourthly, ‘the judgement of other Churches and Christian performance’ requires that any one particular community is open to comparison with other churches in a world-wide communion. Any particular expression should be capable of moving beyond its own boundaries to embrace other traditions across time and space.

Conclusion

My aim in this lecture has been to consider how different aspects of social change have engendered theological movements that have in some way challenged or revised traditional ways of ‘talking about God’.

In order to live faithfully, to speak authentically, talk about God will always be shaped by and attentive to the ‘signs of the times’. Theology has had to deal with fundamental challenges to its own truth-claims and with accusations that it has been complicit with injustices. So this is a story of how theologians have faced up to questions of the very intellectual coherence of ‘talk about God’ as well as the imperatives of whether theology affirms or denies human dignity and the integrity of creation – in other words, to ask whether theology is actually of any earthly use.

But what are the issues for the future? The emergence of Black, post-colonial and Liberation Theologies serves as a reminder that by the second half of the twentieth century, the axis of global Christianity had moved away from Europe and North America, to Central and South America, Africa and Asia. Clearly, the contemporary study of theology needs to be more representative of the contemporary, global religious landscape and reflect new forms of church, new forms of Christian social activism, new ways of imagining God that are emerging.

Secondly, we may also need to start thinking about theology beyond the Anthropocene – from the era of human culture and impact, towards a theology that reflects our growing understanding of the autonomy and integrity of non-human creation. Do we need new ways of speaking about the universe and God as creator, that fosters a deeper respect for the environment and the challenges of global climate emergency?

Thirdly, theology’s traditional basis in reading and writing texts may lead us to misperceive lived Christian theology as simply a matter of ideas rather than practices. We need to explore the links between theology and forms of expression such as literature, music, and the visual arts, as reminders that ‘discourse’ or ‘talk’ about God can take many forms beyond language. Worship, prayer and sacraments are also material expressions and embodiments of speaking about and to God.

And this notion of theology beyond words leads me to a final observation, rooted in another paradox. In the Hebrew Bible, the Holy One is seen as the one who creates through speech, through utterance, through the power of – language. It is words that call all reality into existence. And yet that same God is also depicted as ultimately beyond human imagination or speech – the one who forbids idolatry, or the human inclination to believe that their images or concepts can ever capture the totality of divine reality. Whatever and whoever God is, they are beyond our comprehension. So when we talk about God, then, we should be mindful both of its capacity to build worlds and speak meaningfully to its context; but also that our images and words can never exhaust the infinite mystery of God. It reminds us that negative or ‘apophatic’ traditions are also an important part of the theological canon. It tells us that ultimately, talk about God must end in silence — which seems like an appropriate place for me to end.

Further Reading

Karen Armstrong, A History of God. Vintage, 1993.

James H. Cone, A Black Theology of Liberation, New York: Orbis (1970), 40th anniversary edition, 2010.

AveryDulles,ModelsofRevelation(1983),Maryknoll,NewYork:Orbis,2nd Edition,1992.

Victor Ezigbo, Introducing Christian Theologies. Cascade, 2013.

Elaine Graham, Heather Walton & Frances Ward, Theological Reflection: Methods. SCM, 2nd Edition, 2019.

Elizabeth Schüssler Fiorenza, In Memory of Her: a Feminist Theological Reconstruction of Christian Origins. New York: Crossroad, 1983.

David F. Ford and Rachel Muers (eds), The Modern Theologians: an Introduction to Christian Theology since 1918, 3rd Edition, Oxford: Blackwell, 2005.

Gustavo Gutiérrez, A Theology of Liberation (1973), Revised Edition, London: SCM, 1988.

Arthur T. Hennelley, 1990, Liberation Theology: A Documentary History. Maryknoll, NY: Orbis.

Mike Higton & Rachel Muers, Modern Theology: a critical introduction. Routledge, 2012.

Gordon D. Kaufman, In Face of Mystery: A Constructive Theology, Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1993.

Philip Kennedy, A Modern Introduction to Theology: new questions for old beliefs. I.B. Tauris, 2006.

Kwok Pui-lan, Postcolonial Imagination and Feminist Theology. London: SCM, 2005.

Rosemary Radford. Ruether, Sexism and God-Talk: Toward a Feminist Theolog (1983), Boston: Beacon Press. 2nd Edition, 1993.

Nick Spencer and Hannah Waite, ‘Science and Religion’: Moving away from the shallow end. London: Theos, 2022 (https://www.theosthinktank.co.uk/research/2022/04/21/science-and-religion-moving- away-from-the-shallow-end).

Miroslav Volf, Captive to the Word of God: Engaging the Scriptures for Contemporary Theological Reflection. Wm B. Eerdmans, 2010.

2 Comments

I was struck by an absence of reference to the Bible. Traditional Christianity

regards the Bible as being in some sense from God and as being – again in some sense – reliable about the nature of God and about the Jew we call Jesus. It is neither of those things. It is simply a book, a remarkable one, but with no more – and no less – insight about God than other human writings.

All we know about God is what we learn by looking at the puzzling and difficult world that he has given us – which gives us a very different God to the one we have believed in. And all we know about Jesus is what we can discern through the layers of dubiously transmitted material in the New Testament – unlikely to be reliable about that strange mission-impelled man who still manages to speak to us and calls us in some sense to follow him.

Transforming our Christian faith by accepting these commonplaces of modern knowledge should go alongside transforming it with our knowledge of how the world actually works.

Dear Alan, Thanks for your post. I did actually identify Scripture (the Bible) as one of the primary sources of theological understanding in the first part of my lecture. And also indicated how many modern theologies engage with the Bible — such as Black theologies drawing on the Exodus narrative, for example.