Watch Back: Dr Iain McGilchrist

November 11, 2022

Alison Webster: People, Power and Participation

November 15, 2022This post is a plug for the talk by Iain McGilchrist which went live on Friday. Entitled ‘The Brain and a Sense of the Sacred’, it’s still available here.

McGilchrist is best known for his book The Master and His Emissary. It’s left brain right brain stuff. I can’t possibly summarise his talk, let alone his massive books, but I offer a theological appreciation of it.

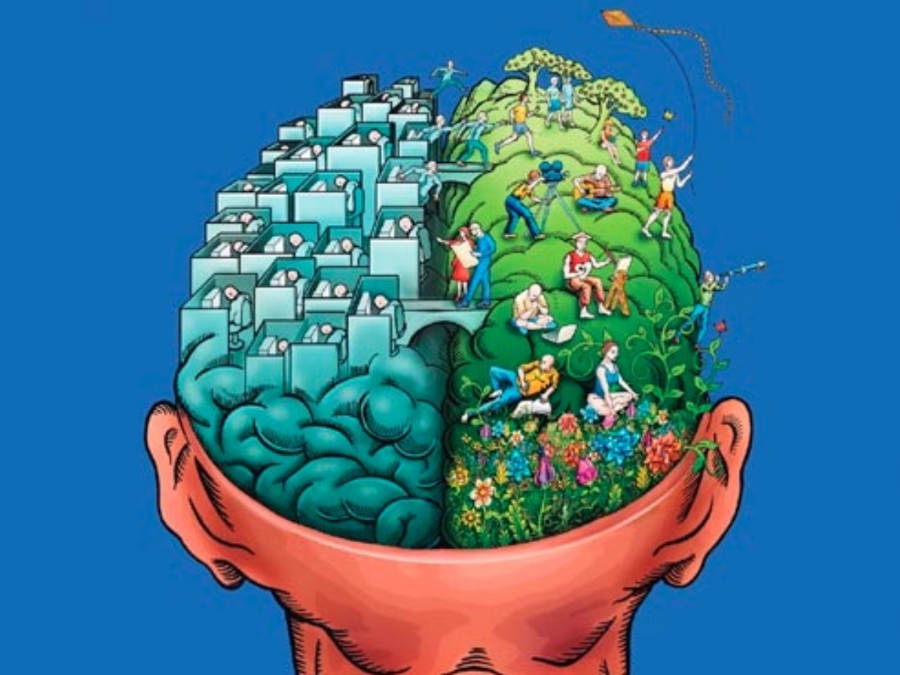

The ‘master’ is the right half of our brains and the ‘emissary’ is the left half. As we evolved we had to learn to do two things that are difficult to combine: to be aware of what is going on around us while at the same time focusing on specific details. The left brain, for example, may have to examine a piece of ground very closely to spot whether anything is edible while the right brain keeps an eye open all around in case there are predators.

More generally the left brain does the detailed calculations while the right brain sees the big picture. McGilchrist’s point is that the left brain is an essential servant but should not become the master. Much of what is wrong with modern society is that the left brain has become the master. We are over-impressed by information that can be counted and measured, and activities that can be shown to achieve practical results.

But the left brain isn’t comfortable with things that can’t be measured and defined. Because we today are over-influenced by left brain thinking, we are not so good at relating to what goes beyond them: values, meaning and the sacred.

Job

I am reminded of a passage in the biblical book of Job. Job is quizzing God about his suffering. He complains that life isn’t fair. God replies:

Where were you when I laid the foundation of the earth?

Tell me, if you have understanding.

Who determined its measurements?

In the book Job is a good man suffering greatly because, unknown to him, God has allowed a heavenly agent (a ‘satan’: the Hebrew word ‘satan’ means ‘adversary’) to mistreat him.

It’s the cultural context that interests me here. During the Babylonian exile some prophets, including Jeremiah, looked forward to a time when the exiles would be allowed home to a time of blessing. This turned into the theory that God would bless morally upright people with good health and wealth. Any suffering would be divine punishment for sin. So when the return from exile did actually happen there was a school of thought that morally upright people really would be rich and in good health.

It doesn’t work, of course. Modern equivalents flourish a-plenty, for example in prosperity gospels and self-help therapies.

The book of Job responds to the fact that it didn’t work. It sounds to me like a good example of McGilchrist’s thesis. The left brain thinkers put together the words of the prophets and the fact that the exile did come to an end. Therefore, it followed, the new era had begun. Illness and poverty would, from then on, only beset sinners. QED.

In the book this was Job’s thinking. His complaint was based on analysing a small part of reality. God’s response was of the right brain type: an appeal to the big picture.

If this is a fair example of McGilchrist’s point (I haven’t checked it out with him) we could easily conclude that things have got a lot worse since then.

When Job was written, everybody knew they didn’t understand how the world works. What people believed was that the world was maintained by some kinds of gods. They disagreed about what the gods were like and how they had created humans, but it was a reasonable assumption that they had given us minds capable of understanding what they wanted us to know.

Principles of knowledge

Later, in the second century Christian debates between Catholics and Gnostics, the Catholic position established the two principles that would later become the presuppositions of science: that the world is ordered, and that the human mind can understand that order.

These principles were, at the time, understood as relative. The absolute is God. God makes the world ordered in the way creatures need it to be, and enables us to know what we need to know for the lives we have been designed for. So left brain calculations had a valuable place, but a limited place: there was much else outside their scope.

Later again, nineteenth-century enthusiasts for science thought they could dispense with God. Instead of God running the world, we need to run the world. So those principles had to be absolutised. The world is absolutely ordered, so there must be a scientific law of nature to explain absolutely everything; and the human mind must be capable of discovering all of them. We therefore need lots of scientists finding out how the world works, so that we can control it.

Today, of course, scientists know that was over the top. The universe is just too complex for the human mind to understand it completely. But at a popular level it’s still common. The idea that ‘we’ know the answers – and when we don’t we will one day – is still immensely influential.

It is as though the left brain’s methods have taken over. The left brain has become the master. What does it do with the right brain? Not much. All that stuff about values, the sacred and our awareness of stuff going on which we can’t explain, is too vague for left-brain thinking.

As COP 27 reminds us how much we are messing up the planet, it strikes me that McGilchrist has an important message about where we are going wrong. It’s the same as the message from God to Job:

Where were you when I laid the foundation of the earth?

We don’t really know how the world works. But we don’t need to. Our task today is not to control the world around us, but to celebrate it and live in harmony with it.