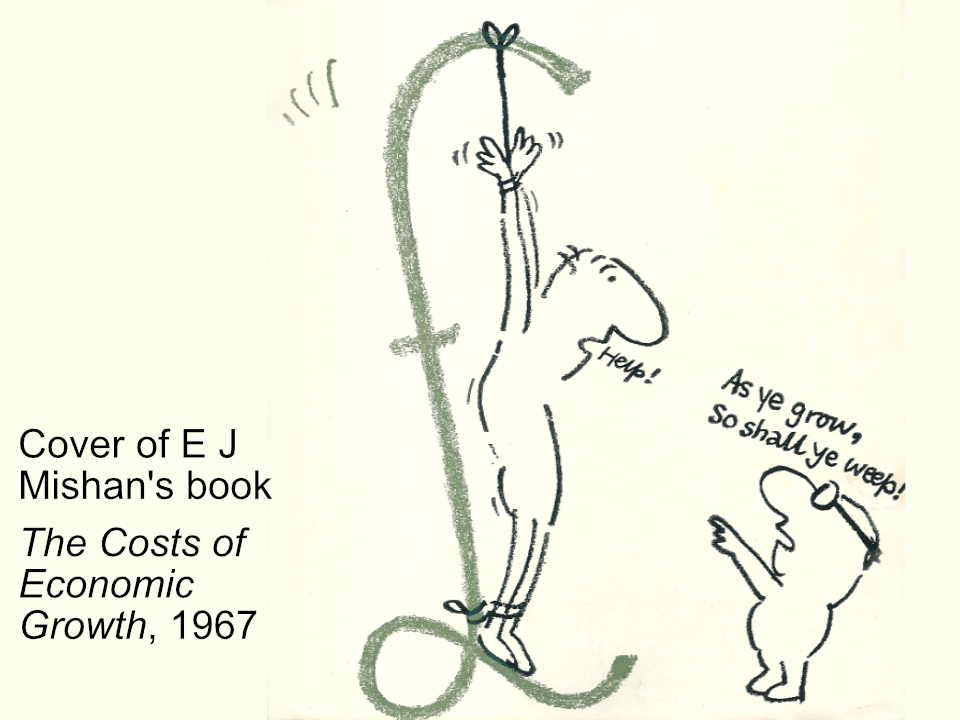

The costs of economic growth

August 6, 2021General Synod Elections 2021 – update from our partners at Inclusive Church

August 18, 2021For over 50 years scientists have been warning us that we need to change our ways. The agreements made at the Paris Conference (COP 21, in December 2015) are largely not being kept. Even if they were, scientists tell us they are not enough. There is increasing public concern, as expressed by new movements like Extinction Rebellion.

Some appropriate changes have been made, but the big decisions are still being guided by the mindset that does the damage. As I write this, my local airport is applying for permission to expand. The most influential voices address the economic impact; the environmental impact is noted but not taken so seriously. Yet if we are to meet our climate targets air travel, far from increasing, will need to be significantly reduced.

Meanwhile the British Government is talking about building more roads, opening a new coal mine, increasing nuclear warheads and punishing protestors more fiercely. Not only in Britain, but throughout the ‘developed’ world, democracies keep electing governments committed to the policies causing the damage. They pay lip service to environmental concern. They agree to changes that don’t challenge their underlying mindset: electric cars, wind farms. But they don’t do anywhere near as much as the scientific community are demanding.

Despairing isn’t going to help. To respond effectively, we need to understand what it is about our values that make us want the wrong things.

Conflicting paradigms

In effect, environmental awareness has reawakened a paradigm – a worldview, or framework for the way we understand the world – which has long been suppressed.

Environmental philosophers usually date the dominant paradigm from around 400 years ago, the time of Francis Bacon. Europe was suffering from successive plagues. It was easy to believe nature was hostile to human well-being. Bacon believed a combination of science and technology could correct the faults in nature which had arisen when Adam and Eve ate the forbidden fruit.

It was a new interpretation of Genesis, but it worked. Today we can look back on centuries of Western self-congratulation. We tell ourselves we are better than the rest of the world because our science has produced useful technologies; we know more; we are more civilised; we have produced more wealth.

We might call this ‘the artificialisation paradigm’. Now scientists are telling us it has led us to damage the environment we all depend on.

There always were good reasons for challenging it. It was the narrative of the victors, not of the vanquished. It benefits some at the expense of others. The greatest benefit accrues to the ruling classes of western ‘developed’ countries. These are the people most determined to keep it going, and they have found ways to control elections so that they stay in power.

We are at one of those points in our history that Thomas Kühn, in a different context, described as a ‘paradigm shift’. The dominant paradigm is no longer convincing. It is increasingly clear that our value systems and ambitions are making things worse. More and more people are looking for a different way to understand and evaluate the world.

A better alternative

It is easy to argue, postmodern-style, that this western paradigm is only one of many. It is harder to argue that an alternative is truly better, and harder still to convince people who have grown used to being surrounded by technological artefacts. I am one, typing this article through high quality spectacles onto a laptop probably manufactured by some Chinese unfortunate working long hours in conditions where I wouldn’t survive at all.

Yet we do have an alternative paradigm with an impressive pedigree. New Testament scholars have argued that Jesus’ teaching about the Kingdom of God appealed to the universalist theme in the Bible. The world had been designed by a supreme creator so that our lives would be a blessing. The world provided enough for everybody to live well. Therefore, making sure everybody has what they need is a matter of justice, not a matter of inventing new technologies.

Those Hebrew scriptures contrasted with the dominant paradigms elsewhere in the ancient near east. Mesopotamians were taught that humans were created to serve the gods with much drudgery and suffering. In Homeric Greece the gods were only interested in specific humans at particular times. It was the Jews who claimed that the world could provide enough for everybody to live well, because that is how it was designed. The early Christians spread the idea more widely. Anthropologists tell us they were right, and the aid agencies tell us it is still true.

The proper role of technology

Bacon’s tradition, of trying to improve on nature through science and technology, was in effect a revival of ancient polytheism. The world of nature was once again deemed inadequate for human well-being. This belief has driven us onto two endless treadmills: the artificialisation of human life, and conflict over resources.

Our current environmental crisis doesn’t prove that the ancient Hebrews and early Christians were right, but it does show that their way of relating to the world around us worked better in practice.

So how do I justify my specs and my laptop? The ancient Hebrews used new technologies when they had reason to do so. There was innovation, as there has been all through history. But they never wanted new technologies for their own sakes. They never thought the world God had given them needed to be replaced with something artificial. If we hadn’t had our 400-year project of suppressing nature we would still have produced new technologies. But we might have been more choosy about them, more careful not to mess up the good things we already had.

Hope for the future

There seem to be two main reasons for our failure to make the changes needed. One is the vested interests of the most powerful people, who benefit most from the present paradigm at the expense of the less fortunate. The other is the ordinary fear of an unknown future, especially among older people like me.

In both cases opposition to change is driven by the paradigm we have inherited. We need to change to a paradigm that values the environment for its own sake. We could then start noticing what, until now, we have been forbidden to notice – that the ever-increasing artificialisation of our lifestyles doesn’t make us happier or healthier.

Things are going to change: what we do, what we want, what we notice and what we avoid. They may change because we take the needs of the environment seriously, and act accordingly. Otherwise they will change because we don’t – in which case our grandchildren will suffer the consequences.

The changes we need may seem a disaster to those clinging to the paradigm we have inherited. But when we let go of it, and learn to think differently, we will find it a blessing. It will benefit us as well as the Earth. It is good news.