Modern Church President elected to Fellowship of the British Academy

July 24, 2021

The environment, the Bible and changing paradigms

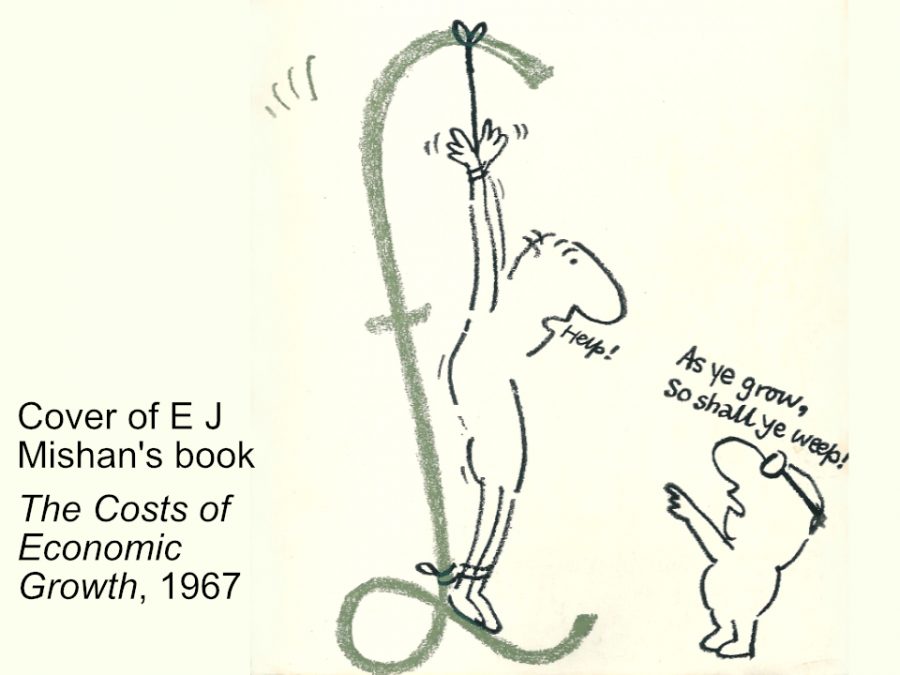

August 18, 2021I have finally got round to reading E J Mishan’s The Costs of Economic Growth, a book I bought for an Economics course in the 1970s. Written in 1965 but not published till 1967 because it was considered too radical, it now looks astonishingly prescient.

As the world prepares for the COP 26 conference on climate change, economic growth looks set to be the elephant in the room.

The dominant story we have inherited is that economic growth, along with new technologies, has vastly improved the conditions of human life. With ever-greater mechanisation we have been able to exploit more of the earth’s resources, produce more and consume more. That economic growth is a good thing is accepted by governments across the left-right spectrum.

For environmental scientists and Green campaigners, on the other hand, economic growth is the driving force behind most of the environmental damage. It constantly increases the world’s rubbish tips, soil erosion, extinctions of species, pollution and global warming.

Public debate responds in two contrasting ways. One is to keep going in the same direction: economic growth has produced lots of goodies, so all we need is a technological tweak to each problem. Electric cars and solar panels will create new green jobs and be good for the economy.

The other is to say we have to change direction. The cult of economic growth has produced disaster. We need to develop a different lifestyle: produce less, consume less, throw away less.

It is here, in this choice between the contrasting responses, that I find Mishan’s book telling. 45 years ago, when it was a new idea that ‘the white heat of technology’ would create ever-changing new opportunities, it was already possible – at least for one economist – to suspect that the losses were greater than the gains.

One of Mishan’s strongest critiques is of the motor car. Cars had completely changed the character of cities, making them noisier, smellier and more dangerous. The Buchanan Report, commissioned by the Government in 1962, argued

that present developments could not be allowed to continue. Unless something was done soon, he warned the public, the usefulness of vehicles in towns would decline rapidly, and pleasantness and safety would ‘deteriorate catastrophically’. He rejected the Government’s then existing policy of small-scale road improvements designed to keep the traffic moving at all costs as being self-defeating. Such ‘improvements’ would, he prophesied, be overtaken by the increase in traffic as soon as they were finished.

Today nobody could deny that he was right. But despite this, the Report’s recommendations were a different matter:

Buchanan goes on to argue that if the present-day town is unsuitable for the motor-car then it must be rebuilt so that we can have the traffic we want along with the amenity we also seek.

Hence those 1960s concrete monstrosities that are now almost universally lamented. They were created, not because they were the best way for people to travel to where they needed to go, but because they would stimulate the economy.

Unless we have travelled to an ‘undeveloped’ country, none of us today has ever experienced a town or city centre that isn’t noisy, smelly and dangerous because of the traffic swirling round it. In the 1960s there were people who had, and who could see the difference. A voice from a past age can tell us what we are missing.

But economists tend to ignore the diseconomies that cannot be measured. Apart from the gendered language this passage of Mishan’s could have been written today:

Business economists have ever been glib in equating economic growth with an expansion of the range of choices facing the individual; they have failed to observe that as the carpet of ‘increased choice’ is being unrolled before us by the foot, it is simultaneously being rolled up behind us by the yard. We are compelled willy-nilly to move into the future that commerce and technology fashions for us without appeal and without redress. In all that contributes in trivial ways to his ultimate satisfaction, the things at which modern business excels,… man has ample choice. In all that destroys his enjoyment of life, he has none. The environment about him can grow ugly, his ears assailed with impunity, and smoke and foul gases exhaled over his person. He may be in circumstances that he will never enjoy a night’s rest at home without planes shrieking overhead. Whether he is indifferent to such circumstances, whether he bears them stoically, or whether he writhes in impotent fury, there is under the present dispensation practically nothing he can do about them.

Privacy, quiet and clean air had become

scarce goods – far scarcer than they were before the war – and sure to become scarcer still in the foreseeable future.

If, Mishan suggests, there had been a law to protect these things – so that industry, motorised traffic and airlines were obliged to compensate the people affected – they would have either found less destructive ways to operate, or closed down altogether.

The noise and pollution he complained about in 1965 is far greater now. For a while, during the strictest lockdown last year, we caught a glimpse of what Mishan wanted to protect; but most of the time we uncritically accept the myth that all that unpleasantness, and the poor health that goes with it, is the price we have to pay for a modern comfortable life.

If COP 26 is to succeed it will need to overcome the bias towards economic growth. It will have to face the fact that the governments of the wealthiest countries have been doing the wrong things.

Changing course, in the way the climate crisis demands, may seem like an absolute disaster. It may feel like a step into a dangerous unknown. But it isn’t. While we have been enjoying the good things economic growth has brought us, we have been accepting – sometimes grudgingly, sometimes patiently, sometimes without noticing – changes which have made our lives more unpleasant.

We have created a vicious circle. The more we trash the environment, the harder it becomes for nature to carry on providing for us. And when we see that it doesn’t, it seems like a reason for doing the worst thing possible: more economic growth.

Human life depends on what nature provides. Nature has always provided enough resources for everyone to live well, so long as we distribute it fairly. It is because we don’t distribute it fairly that many people go without – and then nature seems mean.

To solve our current crisis we need to do what has needed doing all through history: to make sure everybody has enough, and nobody has too much.