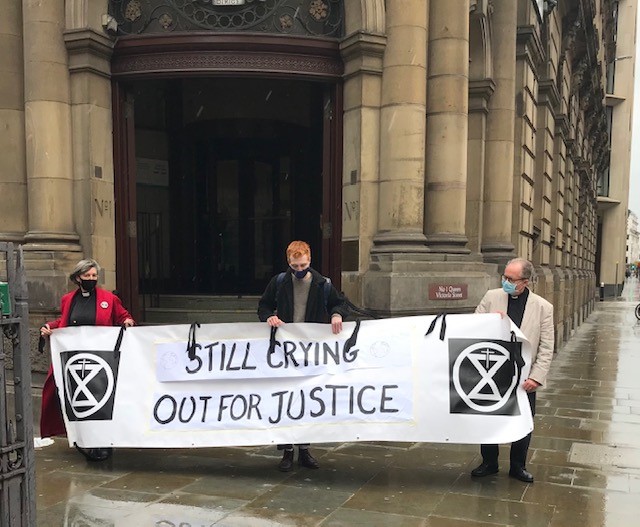

Helen Burnett: Christian Climate Action…. In Court

March 26, 2021

How Covid-19 may have Changed the Church Forever!

April 7, 2021Easter: the most important Christian festival, or the most absurd? Did Jesus really rise from the dead? Physically, as Luke and John tell us, or did he only ‘appear’ as Paul tells us? Does it matter? Two thousand years later, why should anyone care?

What people now think of as the ‘traditional’ or ‘conservative’ Christian view is recent. It is quite alien to the people who claimed to have seen the risen Jesus.

Resurrection today

Today the usual agenda goes like this. Nobody else has ever risen from the dead. Rising from the dead breaks the laws of nature. Only God can break the laws of nature. If you believe in God, God did it. This proves that God exists and that Jesus was unique. On the other hand, if you don’t believe in God, it can’t possibly have happened. The Resurrection stories are wrong. The Bible tells lies. Christianity is anti-scientific.

Here lies the disagreement between fundamentalist Christianity and fundamentalist scientism.

Those who defend Christianity in this way often claim they are being ‘biblical’. But if we want a ‘biblical’ understanding of the Resurrection, we must imagine what it meant to the people who wrote the New Testament.

Resurrection for the first Christians

Back in the days of the first Christians, nobody had even heard of laws of nature. Jews and Christians believed that God runs the world. God does some things regularly, like the sun rising and setting every day, and some things irregularly. The Resurrection was an act of God, but so was the rising and setting of the sun.

To understand their thinking, a good starting point is Peter Gant’s recent book Seeing Light: A Critical Enquiry Into the Origins of Resurrection Faith. Gant explains how the early Christian stories of the Resurrection made sense within the concepts available to them. To them, God lived in Heaven, and dead humans normally went to Sheol, or Hades. Best not to call it Hell, because it wasn’t a place of punishment.

Within that overall picture there were variations. One was that some humans, like Enoch and Elijah, bypassed Sheol and went straight to heaven, or became angels. Another was that the unjustly persecuted would be rewarded in heaven. Another again was that a human-like angelic being would appear from heaven to judge the wicked and begin a new and better era, either on earth or elsewhere.

Gant then turns to how early Christians used those concepts. He takes us through pre-Pauline texts quoted by Paul, Paul’s own contribution, deutero-Pauline texts and the gospels. The different elements are compared: the visions of Jesus as Christ, the claims of his exaltation and/or resurrection, the absence of the body, the contrast with the raising of Lazarus, the empty tomb stories and the later combinations of these themes. As he takes us through the texts it becomes clear that the accounts vary. Sometimes they contradict each other. It is a salutary warning to those who think there is such a thing as the biblical account of the resurrection.

So what actually happened? To summarise Gant’s account in a few words, the disciples had visions of Jesus. Gradually the experiences were developed into the narratives we have, using the exalted terms that characterised contemporary Jewish descriptions of especially holy people.

I find it convincing. Many Christians find it inadequate, but this is because it doesn’t do the job they want it to do. It doesn’t prove that God produced a miracle that broke the laws of nature. To do that, a vision won’t do: the resurrected Jesus had to be a real physical body.

Resurrection and modern science

This is what divides us from the first Christians. Seventeenth century physicists took for granted that God runs the world. They believed God is reliable and runs the world regularly. They described the regularities as ‘laws of nature’.

Later they imagined that the laws of nature operate independently of God. Many people believe this today. It gives us a three-tier worldview, with the laws of nature standing between God and the world. God seems more distant, and doesn’t seem to do anything useful.

When Christians accept this picture, it seems that the only way God can do anything at all in the world is by intervening to break the laws of nature.

Whereas Gant’s account of the Resurrection makes it consistent with modern science, for many Christians the whole point is that it isn’t consistent with science: for them, breaking the laws of nature is exactly what shows that God did something.

What the Resurrection means

This account of the Resurrection, so different from what any of the New Testament authors believed, is now leading many people to conclude that Christianity is a complete waste of time.

It accepts that the universe is run not by God but by the laws of nature. All it adds is that there is a god who has been known to intervene. This is hardly an inspiring claim. Fifty years ago the Charismatic movement saw the problem, and kept insisting that miracles were still happening; but they weren’t convincing. What we are left with is that God did intervene, two thousand years ago. Obvious question: so what?

For those who insist on a physical resurrection, the other claim is the uniqueness of Jesus: only Jesus rose from the dead. Again, it is not the uniqueness claimed by the first Christians. In our earliest account of the Resurrection, 1 Corinthians 15, Paul argued that other Christians would follow Jesus to resurrection. They didn’t, but Paul clearly didn’t expect resurrection to be restricted to Jesus. Again we can ask: if God raised one person from the dead two thousand years ago, why should anyone care?

These two claims – that God intervened, and that Jesus was unique – leave our present lives untouched. Of course, most Christians who believe in the physical resurrection also believe in other features of Christianity, some of which may be relevant to life today. But to treat the resurrection of Jesus as the most important thing about Christianity is to reduce it to a story about wonderful things that happened once upon a time in a faraway land. It offers no response to the state of the world, no consolation to the distressed, no vision of hope for the future. It simply makes a virtue out of believing that amazing things happened two thousand years ago. But it isn’t a virtue. It’s just escapism. It turns Christianity into a fairy story.

For the first Christians, the point was that their own lives were changed for good. Their jumbled-up images of what happened to Jesus after his crucifixion was their way of saying that Jesus had been vindicated. It really was the Kingdom of God into which he had led them, and they were determined to follow.