Abolish A levels

August 12, 2020

Lorraine Cavanagh: Hope Un-deferred

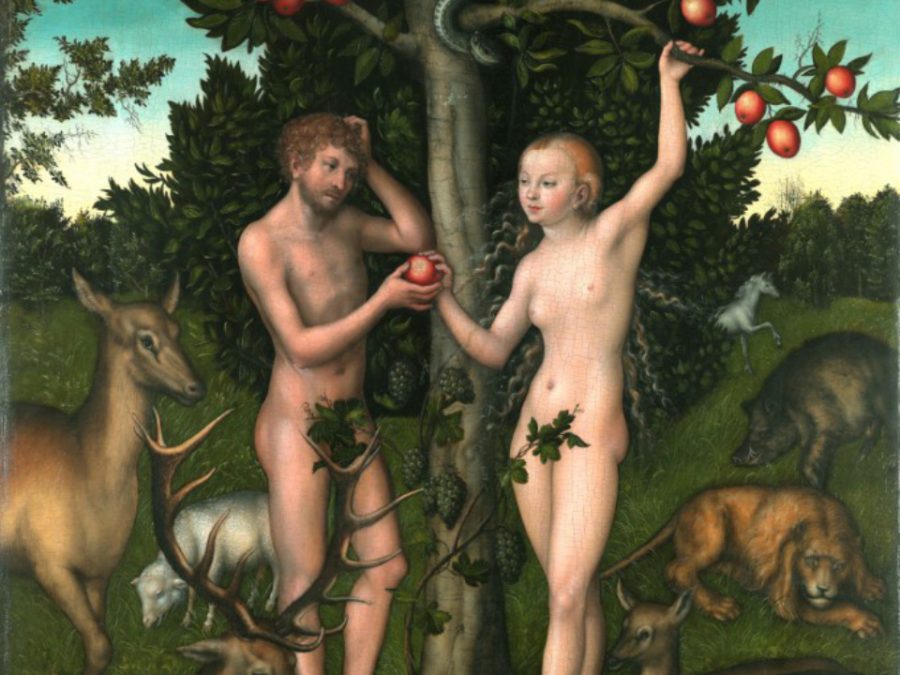

August 27, 2020This post is about the famous story of Adam and Eve eating the forbidden fruit, and what it tells us about our freedom.

It is one of the most misinterpreted stories in the Bible. It is now over a century since Christian scholars of the Hebrew Bible recognised the error. It says nothing about a primeval fall from an originally perfect creation, nothing about the serpent being a devil in disguise. That was a Christian misinterpretation popularised 300 years after the time of Jesus. Jews have never interpreted it like that.

The preceding texts set the scene. (I summarised them in an earlier post ). The first chapter of Genesis asserts that the world has been made by a single good god who designed it to be a blessing for created beings like us. Obvious question: why then is there so much evil and suffering? The second chapter describes God giving humans freedom to choose between living a good life and messing things up.

The third chapter describes it happening. Like the second, it is written in the form of a children’s story – as the talking snake shows. Like good children’s stories, it is not history. It is description of what life is like. From the age of three we all notice opportunities to take a forbidden biscuit when our parents are not looking. We are all Adam and Eve.

Most of the narrative describes who did what and who said what. But at one point it slows down. It invites us to focus on a critical moment. It does something very rare in the Hebrew scriptures: it reflects on what is going on in somebody’s mind. It invites us to pay close attention and sympathise:

So when the woman saw

that the tree was good for food,

and that it was a delight to the eyes,

and that the tree was to be desired to make one wise,

she took of its fruit and ate (Genesis 3:6).

It is as though we are being encouraged to taste the fruit in our mouths, and feel ‘Yes, I would have taken a bite too’.

We are all torn between two responses to wrongdoing. Our own misdeeds, and those of our friends, we understand and excuse. When it comes to other people’s misdeeds we notice the dreadful results and we build up feelings of indignation. It takes maturity to recognise that an act can be both very understandable and very harmful. This is what the text does.

In the story the characters egg each other on, eat the forbidden fruit, feel guilty and blame each other. Thereafter there is a spiral of deterioration: one harmful act leads to another until society is dissolved, first in the Flood and later at the Tower of Babel.

To put it in traditional Christian language, this story isn’t an account of a primeval Fall; it’s an account of sin. Often Christians fail to notice the difference, and speak of a Fall – humans being fallen – when we really mean we are sinful. But when it comes to understanding the potential of human life, it makes a huge difference.

The Fall, properly speaking, was a single event when an originally perfect world went wrong. On this account God’s good creation failed. Evil and suffering are results of the Fall, and there is nothing we can do to stop them. We are stuck with them. Life is necessarily tragic.

This idea has its natural home in polytheism – the belief that there are many gods. In the ancient world most people thought like this. They found it easy to believe that one god made the world and another god messed it up.

But this is not what the text in Genesis says. In the whole of the Bible there are only two references to a Fall (Romans 5:12-14 and Romans 8:18-23) but these are passing mentions by Paul who often referred to pagan beliefs.

The beginning of Genesis is too monotheistic for that. It describes the world as created by the one and only god. God then withdraws from control, giving humans space to choose between good and bad actions.

So God allows the gap between what we do and what we should do. The story makes it sound all so understandable; and from our own experience of life, we know that it is.

This is good news and bad news. The bad news is: we humans are responsible for all that is wrong. We don’t like to know this. We would prefer to blame the state of nature, or the economy. Governments, especially, prefer to pass the buck. This is why, in the fourth century AD, after the Roman Empire had become formally Christian, the story of Adam and Eve got reinterpreted. The imperial government, like governments today, preferred to believe that all that is wrong in the world is caused by forces beyond human control.

The good news is: because humans are responsible, we can do something to put it right. Here is the moral task facing humanity. We are animals with gut emotions driving actions. As we evolved, over the millions of years, we acquired the ability to reflect on our desires, to develop rules of behaviour, condemn other people’s behaviour, and then reflect on our own behaviour. You and I are somewhere along that long physical and moral evolution, somewhere between amoebas and angels. It really is open to us, collectively, to do better. Depending on the way we use our freedom, real progress – progress in goodness – is possible.