The Search: An Exploration of the Spiritual Experience and the Origins of Belief

July 30, 2020

God, Grace and Donald Trump

August 3, 2020As the lockdown eases up, the remaining restrictions still generate anger. What right has the Government got to take away our freedoms? Why shouldn’t I decide for myself whether to wear a mask or invite someone into my house?

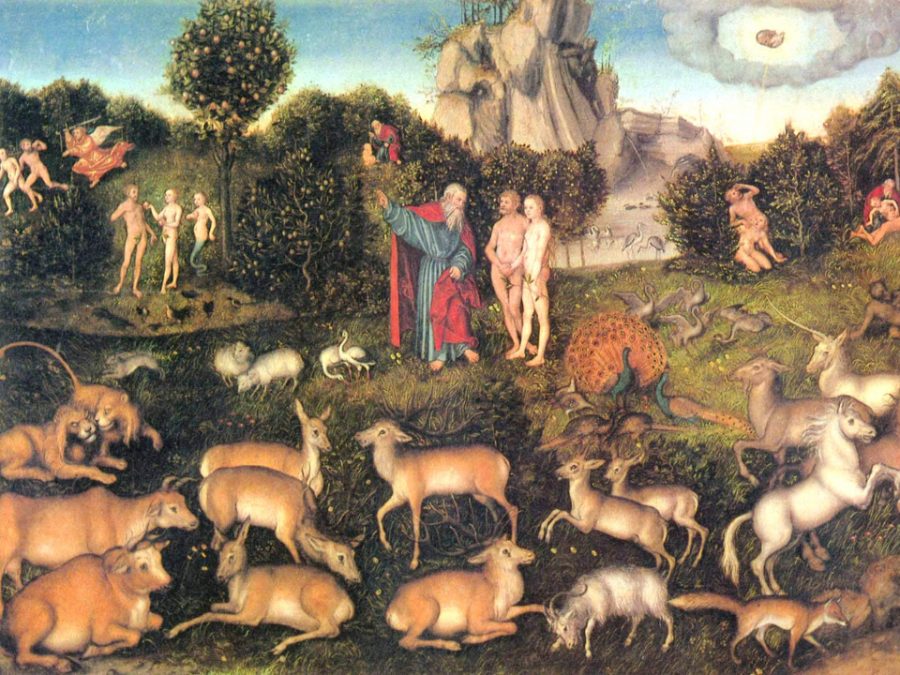

In practice, of course, governments restrict our freedom in lots of ways all the time. A free for all would suit the biggest bullies but deprive others of the freedoms they possess. This post reflects on the moral limits to the use of freedom, drawing on the stories of Adam and Eve at the beginning of the Bible.

Or more precisely, ‘Adam’, which is Hebrew for ‘humanity’. Countless scholars have analysed the first three chapters of Genesis. Drawing on some of them, with the help of John Barton, I described in my Why Progressives Need God how they provide a helpful account of freedom. Public policy would do well to be guided by it.

Chapter 1 of Genesis establishes monotheism: a single god, with no rivals, puts us in a good world and provides everything we need to flourish.

It was probably first written down in reaction against very different accounts of creation. In the big empires of that part of the world, the political establishment taught that humans were created to serve the gods. The gods spent a lot of time quarreling with each other. Different gods contributed in different ways to running the world, which explained why it was often a bit of a mess. On the whole they didn’t care to make life pleasant for us.

At the time Genesis 1, with its more optimistic account of human life, was a minority view. It described life as deliberately created to be a blessing. This raises two obvious questions.

1) If God is so powerful, are we all puppets on a string?

2) Why is there so much evil and suffering?

We should not be surprised if the biblical text immediately offers answers.

Chapters 2-11 of Genesis are written in narrative style. They have the feel of bedtime stories. We should not be put off by this. Good bedtime stories help children to understand what life is like. Not everything is true – talking animals, like the snake in Genesis 3, are a common feature – but children can cope with that.

Chapter 2 describes the four features of human life which, between them, liberate us from divine control so that we are not puppets on a string.

The first two are freedom and morality. The other two, creativity and desire, provide the power and motive to do good or evil. This post only addresses freedom and morality. The key text is Genesis 2:16-17:

The Lord God commanded the man, ‘You may freely eat of every tree of the garden; but of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil you shall not eat.

Ancient Hebrew had very new abstract nouns, so the word ‘freely’ renders a literal ‘eating you may eat’. Here God gives us – Adam, humanity – the power to choose between alternative courses of action.

Immediately the text associates this gift with its all-important significance. God gives us the power to choose not just between Braeburn and Golden Delicious, but between important options. God has designed us in such a way that if we use our freedom well we receive the blessing; but we don’t have to. We can also choose to benefit ourselves at the expense of others. The next few chapters of Genesis, 3-11, then describe how we do mess up, and how one tragedy leads to another.

So the sequence is this. First the authors of Genesis established that our lives have been designed to bless us. It really is possible for everybody to live a fulfilled life. Then they explained why it isn’t always a blessing. We have been given freedom to do harm as well as good. Together with creativity and desire, we live with the tension between self-interest and the common good that characterises moral conflict.

Later on, Hebrew editors decided that these early chapters of Genesis, with their account of the human condition, would make an ideal preface to their other scriptures: the laws stating how kings should govern; the prophets condemning them for not obeying the laws; and the histories attributing their loss of national independence to their disobedience.

Modern nations could do worse than to preface their laws with a philosophy like this. A better life is possible. It comes about when we use our freedom well. Rather than insisting on our right to use our freedom however we want, we should use it for the common good. Every law should be designed to help us do it.

3 Comments

Hi Jonathan Thanks for this, but – I quote ‘Ancient Hebrew had very new abstract nouns’ – should that be ‘few’?

Yes! I’ll do an edit.

Hi Jon,

In your opinion is the freedom positive or negative freedom?