Time After Time

October 28, 2021

Who creates wealth? The market?

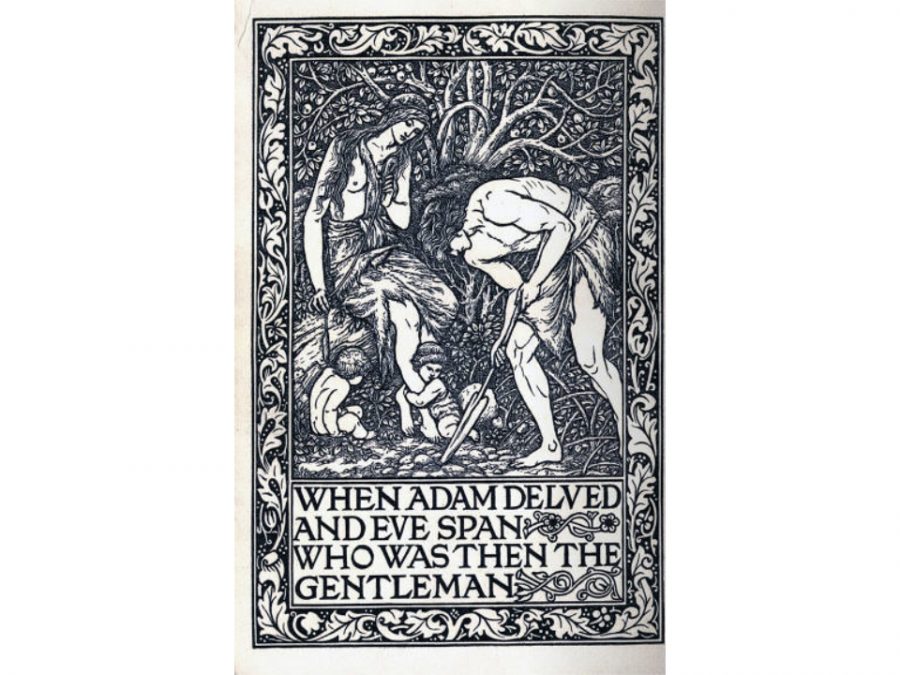

November 13, 2021What do we value, and how do we measure it? This post is part of my series on how economic theories have moved further and further from the egalitarian principles in the Bible and early Christianity.

With the labour theory of value we reach the point where human workers, rather than God or nature, come to be seen as the real wealth-creators.

Economics as a science

Isaac Newton showed that, by studying what happens in the natural world, it is possible to establish regular laws of nature well enough to predict future events. Adam Smith wanted to do the same with economics. Since he also wanted to increase the nation’s wealth, he would need some way to measure it.

The only available unit was money. Money changes hands when people pay each other. Thus arose the labour theory of value. What humans do when we pay each other counts as creating value simply because it can be measured in terms of money. Human labour comes to be seen not as one of the resources nature provides, but as the fundamental source of wealth.

Natural goods

Money doesn’t change hands when we breathe air, grow our own food, admire a beautiful sunset or go for a swim in the sea. If we continue to believe that these things are provided by God or nature, we can’t measure them economically.

It’s only the circulation of money that economists can measure. Of what they cannot measure they should remain silent.

But they don’t. Instead what we get is the principle ‘I have a hammer so whatever I see must be a nail’. What our measuring systems can measure counts: what they can’t measure doesn’t count.

So the growth of plants and the activities of animals are treated as valueless until they get ‘developed’ by some human industry. When clean air and water are judged valueless, polluting them doesn’t seem to reduce their value. It’s absurd, but this is how businesses operate. And governments encourage them.

It was another break with the Christian tradition. In fact it is a break with all earlier accounts of wealth. From this point on it became possible to believe that the value of any item can be related to the work humans invest in producing it.

The change didn’t happen all at once, and nobody ever lives as though it was true. But the commercial classes encouraged the economists, and now it is a rare government that does not do their bidding.

For some specific calculations the theory can be helpful, but as a way of understanding value it’s disastrous.

Neoliberals replaced the labour theory of value with the subjective theory, in which the value of any item is whatever it can fetch in the market. But this doesn’t reduce the scale of the change.

Only very recently, in the light of environmental destruction, have some economists begun to question it. They still face an uphill battle against the political-economic establishment.

The damage

In the dominant growth-driven paradigm left and right alike appeal to the mountains of mathematical calculations constantly being produced. Since there are so many, economists can easily spend their careers studying them without taking seriously that they only measure exchanges of money that have been recorded. Many exchanges are not recorded, and most of our activities do not involve money at all.

A large proportion of the population do not produce anything to sell: babies, the elderly and many of the ill and disabled.

Our economic paradigm encourages people to complain about money spent on ‘scroungers’ and those who do not contribute to the economy, as though contributing to the economy was the entire purpose of human life. It is as though ‘we’, or the economy, would be better off if all those non-contributors dropped dead. Most people wouldn’t express their views as bluntly as this, but this is the direction in which our dominant economic paradigm is pushing us.

Conclusion

The mathematical calculations of economists never reach the point of telling us what we should do. This is partly because so little of what goes on can be economically measured, but mainly because knowing what to do depends on our values, not on our sums.

Dependents we will always have with us. They are a blessing, not a misfortune. If their existence stops us doing what we want, we are wanting the wrong things.

We need to do our wanting differently. Many older traditions, including Christianity, have the resources to offer a better way. We need to rediscover them.